The new vinylists: Shoddy Goods 003

18

Hey, Jason Toon here with another issue of Shoddy Goods, the newsletter about the stuff people make, buy, and sell. Through booms and busts, passionate vinyl enthusiasts have kept records alive. Now some of them are getting into the business of manufacturing vinyl records. It’s not easy, but true love never is.

If I met Steve Lynch under other circumstances, I wouldn’t think “manufacturing tycoon.” Tousled hair, well-cultivated mustache, comfortably stylish, probably cooler than you without taking it too seriously. Definitely cooler than me.

Same with Alex Stillman and Sara Pette. On our video call, the two Minnesotans are funny, incisive, and absolutely unpretentious like the Midwestern punks they are. Ever met a riot grrrl who runs a factory?

But unlikely moguls like them are behind new plants around the world, often the first of their kind in their locations for decades. It all makes sense because the product is the love child of light industry and heavy riffs: vinyl records.

“I definitely count our blessings because it’s probably a crazier idea than I realised,” Lynch tells me at Program Records, the pressing plant he co-founded in Melbourne, Australia. Nearby, Radiohead’s new Kid A reissue is being assembled by hand, one shiny black record at a time being slipped into the paper liner and gatefold sleeve. “I didn’t realise the scope when we started of what we were actually doing.”

#nofilter

The bottleneck blues

Lynch first noticed a problem around 2012 while working in a Melbourne record store.

“We were getting titles in from local bands that would sell out,” Lynch says. “By the time the repress would become available, it would be sort of nine, ten months, a year later, and by that time you’re thinking ‘maybe the heat on this record’s died down a bit.’”

See, when major labels stopped making vinyl, record sales cratered. What had been a $2.5 billion industry in 1978 bottomed out at $10.6 million in 1993: a staggering 99.6% decline.

But 99.6% dead is not quite 100% dead. A few pressing plants scraped by on small runs by indie labels and DIY outfits. In the early '90s, your band could press up 1000 copies of a 7" EP (about 12 minutes of music) for about $1500 and sell them at your shows for $3 each.

Those 7" sales helped keep your tour van running and gave curious fans a cheap taste of your music. That’s what my punk bands did. That’s what every punk band did.

As always, though, underground cred turned into mainstream cool. By the mid-2010s, Adele and Taylor Swift blockbusters were shifting significant units on vinyl. In 2021, vinyl sales topped $1 billion for the first time since 1985.

And that was more than the remnants of the once-mighty record-pressing industry could handle. Wait times for indies to get records pressed blew out from weeks to months and even years. The music communities that had kept vinyl alive were increasingly shut out of the vinyl revival.

Lynch’s conversations about the bottleneck with a regular customer named Dave Roper gradually turned from griping to strategizing. Maybe somebody should do something about this…

Vinyl tadpoles: future records in pellet form.

Bureaucracy, a pandemic, and 4 AM Skype calls

“I just was really just talking without knowing what I was saying,” Lynch says. “Equipment was impossible to come by as an outsider in like 2012, 2013, 2014.”

Two things opened the door to the possibility. Roper, who had founded the successful Australian bag brand Crumpler, decided to invest in starting a new pressing plant. And a new generation of companies started bringing modern pressing machines to market.

In 2017, Lynch and Roper ordered two new presses from VirylTech, a Toronto company, and found a space in the perennial music hotbed of Melbourne’s Inner North.

Two years later, they were still waiting for permits for the electrical upgrades the plant needed. But Lynch also realized how much he had to learn, and how few people were around who could teach him.

“In a trade, you’d do an apprenticeship and you’d learn how to do it,” Lynch says. “But because there wasn’t an industry that allowed you to learn, what I did was worked in the factory in Canada. Stayed with a friend in Toronto and I’d just go press records with VirylTech.”

Finally, in late 2019, all that was left was for VirylTech engineers to come to Australia and help Program set up their new machines. They got their visas to visit… in early 2020. Just as the world was shutting down.

So Program Records became the first record pressing plant to be set up over 4 AM Skype calls. By webcam and worklight, slowly but surely, Lynch and his friend and technician Luke Marinovich got it done. The wax started rolling by the end of 2020. Program Records was finally, impossibly, in business. It was the first new pressing plant to open in Australia in 30 years.

Your friendly neighborhood pressing plant

Sara Pette and Alex Stillman. Yes, they are as badass as they look.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, another record store employee was coming to the same conclusions. “I was complaining to my dad,” says Alex Stillman, who was working at the venerable Minneapolis punk record store Extreme Noise in 2020, "about the resurgence of vinyl not actually being that awesome for us specifically. We were getting less stock in regularly, because the indie labels weren’t being able to press as much. We had less customers coming in because we had less new stock.

“And he was like ‘well, why don’t you just make them, then?’”

It wasn’t idle talk. Stillman’s dad had a manufacturing background himself. And her friend and former bandmate Sara Pette just happened to be looking for something new.

“I sort of was freaking out because the pandemic happened and my (pet care) business at the time was tanking,” Pette says. “Then the backlog of records, you know, production time was up to a year at that point. So that felt like a good time to get into the business just because there was seemingly no shortage of work.”

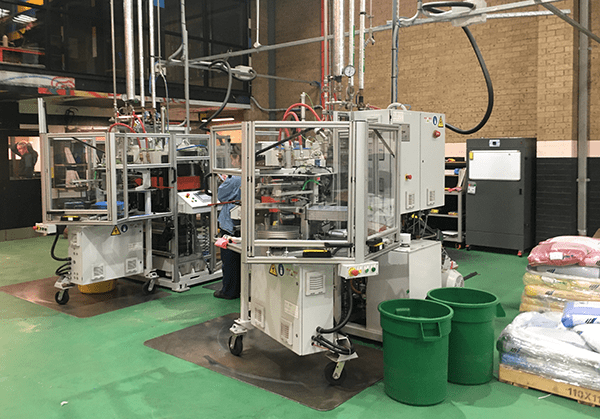

Outta Wax was born. With Pette’s brother John as their third partner, they settled on presses from the German firm Newbilt Machinery, for their combination of ease of use with the ability to manually do custom things like splattered-color vinyl.

“It’s just a good beginner one anyway,” Pette says. “Like everything’s labeled really nicely, the interface is pretty user friendly.”

“Probably because it’s German,” Stillman jokes.

The hardest part, they say, was getting the Outta Wax space outfitted for manufacturing. “I think the construction world was the biggest hurdle because we’re short women that dress unconventionally,” Stillman says. “The tradesmen have all been great. It’s more like the mechanical engineers and designers and the middle managers.”

“We didn’t anticipate the degree to which we’d be taken for a ride,” Pette agrees.

“This is the thing we’re going to do to fight back”

Other shocks were even harder to predict. “The price of the stampers” - the metal molds that shape the hot wax into a record - “got crazy because they’re made of nickel and the price of nickel went up because there’s a ground war in Europe,” Stillman says. “It’s interesting being in manufacturing and seeing how geopolitical stuff can affect your business.”

Then, last year, a horrific tragedy hit their Twin Cities punk community. A mass shooting at a backyard punk show killed one person and injured several others. Stillman was there. Some of the victims, including the one who died, August Golden, were friends of theirs who had been helping with Outta Wax.

What makes the DIY punk scene such a safe harbor is that it’s simultaneously open and tight-knit. A shooting like that could have shredded that mutual trust and sense of belonging. Stillman says Outta Wax provided one focal point to keep the community together.

“Being able to open and have this for our community just feels like a win in the wake of something like that,” she says. “It was definitely something that our friends were rallying around immediately after that. Like, this is the thing that we’re going to do to fight back.”

So they did. This year Outta Wax became one of the 40-plus plants currently pressing records in the U.S., double the number from just ten years ago.

Too much pressure?

Self-taught record enthusiasts weren’t the only ones to notice the opportunity in the vinyl backlog. The major pressing plants also added tons of capacity over the last couple of years, with something like 300 new pressing machines coming into service. Lately, the talk around the vinyl industry is about too much capacity, including layoffs of plant staff.

Weird how sometimes magic happening looks a lot like hard work.

Such a tsunami could threaten to swamp the small, locally-rooted makers. While a big pressing plant might turn out 160,000 records a day, a typical day at Program is more like 1,500, and their peak is around 3,000. Outta Wax is starting with a steady 300 daily.

Program’s six-month lead time is now down to eight weeks. “The scarcity of capacity meant that we were the belle of the ball” for a while, Lynch says. “Obviously major legacy plants in Europe and North America added a lot of capacity which has taken a lot of shine away from the boutique pressing plants like us.”

Too small to fail

But the new vinylists are betting that their community roots will carry them through the booms and busts at the corporate level of the industry. Even though Program now presses for major labels along with local indies, Lynch says their personal connection to the Melbourne community will remain their bedrock.

“Records are a romantic thing for people,” he says “whether it’s a small band doing 150 or whether it’s a big band we’re working with. It’s always an emotional thing for them.” A local band like King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard can tour the world, but still get their records pressed right in their own neighborhood.

“Also I have to see these people if I want to go to a gig,” he laughs. “Everybody (in the Melbourne scene) knows everybody, so you’ve got to be good to everybody.”

Stillman and Pette agree that staying human-scaled and community-focused is the surest way to survive.

“It’s not a business that anyone should get into to get your standard, like, 20% return on investment in two years,” Stillman says. “It’s like, you love this thing and you want it to exist. And that’s why you should be doing this. People who aren’t doing it for that reason tend to not last very long.”

That’s what really stands out to me about these folks: despite spending their working hours thinking of records as manufactured units, they haven’t lost that spirit of wonder, that awe of how miraculous it is to capture human expression in a physical artifact that can move people across continents and decades.

“I would say it this way,” Lynch says. “I know how it works, but I don’t know if I understand it.”

Is there anything you love so much, you’d go into the business of making it? Sing it in the community discussion for this issue. And if you’ve been missing Shoddy Goods, catch up with these stories:

The biggest, weirdest advertising flop in Olympics history

Does Temu creep you out? It’s worse than you think

One more thing: I had a ton more material than I could fit in here. Would anybody be interested in our outtakes and leftovers? Let us know!

- 13 comments, 5 replies

- Comment

It’s getting easier to find new albums lately.

Ordering from Ebay for used albums, they are usually worse condition than described.

@daveinwarsh In many cases. the originals were never as good as what’s being produced now because pressing facility air filtration and dust control actually matters to the folks who are making the new stuff. Even DG wasn’t as diligent as these new outfits.

That said, I’m getting really close to selling my turntables.

@daveinwarsh @werehatrack I sold my turntable years ago, eventually regretted it, and recently bought a new setup. Not quite as nice as what I had before (which I could never afford new, and no longer have the patience to search for second-hand) but ahhhh, so good.

I won’t be able to read it for another few hours but just wanted to say this issue is easy for my decrepit eyes to read on my phone. Thanks, y’all!

I liked the words “99% dead is not dead.”

@apitrone If it was completely dead, the only thing to do would have been to go through its pockets looking for loose change.

Jason, this was awesome. Thanks for sharing it with us.

POKER! JOKER! NOT MEDIOCRE! AWESOME!

I could see getting into making hot sauce, but it would have to be as a hobby. There isn’t nearly the need in the market that there was for vinyl, although I guess anybody can develop a following and create their own niche.

I’m excited for a new generation to get into vinyl and discover how much it f****ing sucks as a medium. Remember to keep your records out of sunlight and cars, don’t stack anything heavier than a graham cracker on top of them, and hire a microsurgeon to make sure the needle drop doesn’t scratch them (but it will).

It just requires too many precautions. It’s like the Mogwai of media.

… There’s outtakes?

A year or two ago I finally got myself a big boy turntable. Not super high-end, but nothing you’d find in Target. I’ve got a Denon receiver that is far too modern to have phono inputs, so I had to get a pre-amp to put in between the two. I never got it sounding like what I was hoping for. When my dad passed earlier this year, my mom was just going to toss his old stereo, but I said, let me take a look first. It was an old Sony receiver from the early 90’s… it was probably pretty fancy back in the day and sure enough it had phono jacks. And a pair of Bose 301s in great shape. I put it all together behind my bar and it’s only function is to play records. And it sounds SO good. Love me some vinyl!

I agree that used vinyl is generally disappointing. But it is getting easier to find new in almost any genre. Not for everyone or every event, but sometimes I just enjoy the semi-OCD ritual of cleaning, dusting, playing and flipping. Nothing sounds better or fuller.

@thenance77 I typically listen to older stuff like Jackson Browne, Styx, Supertramp, etc… I’m finding new-ish vinyl on Amazon for a reasonable price. Yesterday I got two new albums that will be hitting the turntable soon. Hootie & The Blowfish - Cracked Rear View and Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill. Two albums I think are completely solid from the first track to the last

“Too Small to Fail” is the most interesting idea here - with well-made small (read: possible to capitalize) equipment becoming more and more common in many industries “cottage factories” have emerged in a lot of directions.

Currently spinning.

Clear vinyl on a clear platter. Kind of cool to see the bamboo plinth through both

One more thing: I had a ton more material than I could fit in here. Would anybody be interested in our outtakes and leftovers? Let us know…Ummm yes please!!! I love this

‘Back in the day’ I had about 10 linear feet of vinyl that got dutifully moved from one house to the next (about a dozen times or so) until we ended up in AL. While doing some extensive remodeling we moved all of it into the shop (spring time so not too hot yet) and then we got enough rain over several days to sink the backyard (and Yes, the shop) in about 6-12 inches of water. Needless to say, they all got trashed. I was VERY distraught as you can imagine and even toyed with the idea of trying to recover them, but had to give that up when I saw the damage to the covers, sleeves and actual labels…