From a King to a Jack: Shoddy Goods 004

8

Hey, Jason Toon here with the fourth issue of Shoddy Goods, the newsletter about the stuff people make, buy, and sell. Fast food is one of America’s most ubiquitous cultural exports. But when a U.S. hamburger giant tried to expand to Australia in the early 1970s, they found out they couldn’t “have it their way.”

When I moved to Australia, I noticed a lot of the usual U.S. fast food chains: McDonald’s, KFC, Subway. And then a bunch of local Australian ones: Red Rooster, Zambrero, Schnitz (Aussies love them some chicken schnitzels).

But there was one that was neither here nor there. Both familiar and strange. Everything about it said Burger King: the logo, the “flame-grilled” slogan, the color scheme, even the Whopper. But it wasn’t called Burger King.

This is the story of Hungry Jack’s

What timeline have I stumbled into?

The Yank who crowned himself king

The year was 1959. A lanky, energetic American named Don Dervan was seeking his fortune in London. What he found was a wife. But Jean McEntee wasn’t a local, either. One thing led to another and before long, the young marrieds were on their way to set up house in her sunny hometown: Adelaide, South Australia.

I don’t know what was going through Don Dervan’s mind when he made that 10,000-mile journey to a city he’d probably never heard of before he fell in love. But I do know that Australia at that time was practically begging immigrants (white ones, anyway) to come claim a stake in a booming land of opportunity. It must have seemed like wide-open territory for an enterprising young Yank.

Don looked around and noticed a strange gap in the Adelaide market. A gap that an American like him was uniquely positioned to fill. You couldn’t get a hamburger around here.

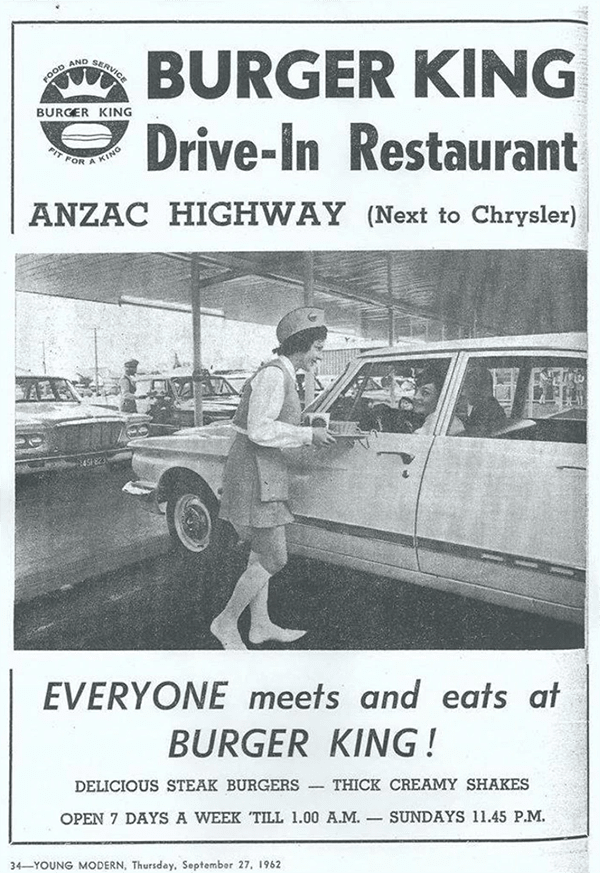

By 1962, he’d opened his first drive-up restaurant, serving up a side of American glamour with every order. Miniskirted waitresses glided up to patrons’ cars bearing bountiful trays of burgers, fries, and shakes. And the grill kept sizzling all the way to the outrageously late hour of 1 AM. Don knew it would be a sensation in staid Adelaide, and it was.

As for what to call it, well, why reinvent the wheel? A fast-food chain in Florida happened to already have the perfect name, and it must have seemed unlikely they’d ever even hear about Don’s venture, much less expand all the way to Australia. So Don registered the Australian trademark for Burger King. His and Jean’s dynasty grew to 17 restaurants around South Australia, and a house full of kids in the Adelaide sunshine.

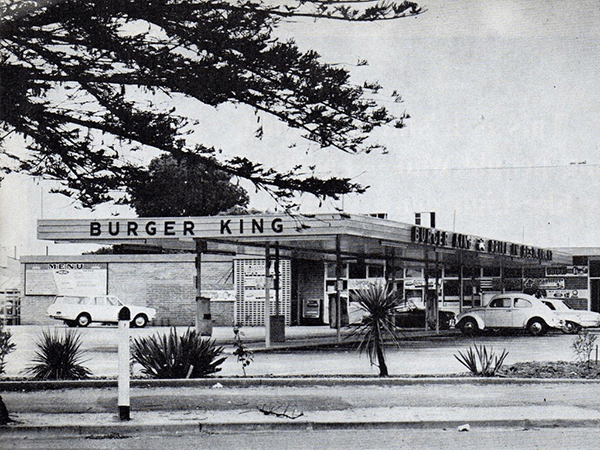

The royal embassy in Australia.

A Canadian rival fires up the grill

But Don wasn’t the only North American to see opportunity in Australia’s stubborn lack of fast food. On a visit to Australia, a Toronto insurance salesman named Jack Cowin saw Sydneysiders lining up at a Chinese restaurant that was one of the few carry-out places in town.

The 26-year-old dashed home, rounded up money from some fellow Canadians, and moved back to Australia with his wife and child. In 1969 he bought the franchise rights for Kentucky Fried Chicken in Perth, Western Australia, often cited as the most remote major city on Earth. The nearest city of at least 1 million people is Adelaide, over 1300 miles away. And Cowin sold the fastest chicken in town.

(A funny side note: by this time, the menu at Dervan’s Burger King included an item called “Kentucky Golden-Fried Chicken”, complete with the slogan “It’s finger-lickin’ good”. He was an equal-opportunity pirate.)

If Don Dervan was a king, Cowin became an emperor. An oligarch, even. He aggressively expanded his holdings over the next 50 years not just in fast food but areas like ranching and media. Today, now 82 years old, he’s one of the richest tycoons in Australia, with a net worth estimated at A$4.36 billion (about US$2.85 billion).

But all that was still in the future in 1971, when Cowin approached the Pillsbury Corporation to inquire about the Australian franchise for their booming competitor to McDonald’s, Burger King. Pillsbury was happy to sell Cowin the franchise rights. But about the name, well…

One man’s pancake is another man’s Whopper

Cowin and Pillsbury soon found that Don Dervan’s claim to the name Burger King was unshakeable. Sure, the original Burger King had it first. But trademarks don’t necessarily cross national borders. As far as Australian law was concerned, Don Dervan was the one true King.

These days, international “domain squatting” is a well-known phenomenon, including in Australia. Entrepreneur brothers Gabby and Hezi Leibovich jumped on groupon.com.au early and sold it to Groupon in 2011 for an undisclosed sum upwards of a quarter-million dollaridoos. (Full disclosure: I used to work for the Leiboviches, I remain friendly with them, and I like them a hell of a lot more than Groupon.)

But in the less connected world of 1971, this was pretty unusual. The only thing Pillsbury could think to do was present Cowin with a choice of other trademarks they already owned for him to choose from. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this franchise-hungry Jack settled on (and settled for) the name of Pillsbury’s well-known pancake and biscuit mix, Hungry Jack. (That’s “biscuit” in the American sense.) The possessive S made it the name that would help fatten up generations of Aussies.

Architecture. Fashion. Cigarette smoke, probably. This was Hungry Jack’s golden age.

Missing out on the Burger King brand didn’t seem to slow down Hungry Jack’s. Cowin’s first franchise in Perth grew into a chain of more than 400 outlets across the country, making Cowin the biggest Burger King franchisee outside the United States.

Pillsbury offered to buy Don Dervan out, and he was happy to sell his restaurants in the early 1970s, including the original location. (There’s a Hungry Jack’s there to this day.) But not the name: he thought maybe he’d still like to do something with it. He and Jean cashed out and moved the family to Georgia. As Dervan settled into American life, he let the trademark lapse in 1991.

Burger King (no longer owned by Pillsbury) snapped it up and told Cowin the good news: hey, you can call your restaurants Burger King now! But Cowin said not so fast.

Food fight!

By then, Hungry Jack’s was so well-established in Australia, Cowin thought there was more value in the once-unwanted name. Burger King Corporation disagreed. Strongly.

So strongly, in fact, that they tried to make the name change a condition of renewing Cowin’s franchise agreement in 1990. When that didn’t work, Pillsbury bought up some Hungry Jack’s outlets from another franchisee and renamed them Burger King in 1993, announcing plans to aggressively expand in coming years. At this point they were competing against their own franchisee.

Then in 1995, Burger King tried one more cutesy legal maneuver: they stopped granting approval to any new stores in Australia. Oh, will you look at that: Cowin was now unable to fulfill the condition in the agreement that he open at least four new outlets a year. Burger King moved to terminate Cowin’s contract because of this “violation” that they themselves had engineered.

The result was the kind of court case that has its own Wikipedia page. The verdict: total victory for Cowin in 2001. Burger King backed off. And that’s how a country with an actual king became the land without a Burger King.

As for Don Dervan, he and Jean lived to a ripe old age back in the States. He died in 2016 in - of all places, I kid you not - Melbourne, Florida.

Is it just me, or does a fistful of French fries sound really good right now? Pontificate and reminisce in the discussion thread for this issue. And catch up on these Shoddy Goods stories if you missed 'em the first time:

- 11 comments, 17 replies

- Comment

What I know is that from my exposure to Australian YouTube personalities, I find the Australian attitudes towards a lot of things much more appealing than the ones here.

@werehatrack And my all-time favorite TV commercial was for Carlton Draught beer, and it was just called the Carlton Draught Big Ad.

@werehatrack Love it!

@callow @werehatrack That was great!

They’re all a bunch of bogans!

Just kidding… I’m sure they’re all pretty great, just not as great as the New Zealanders.

Need to fill my ute at the bowser before heading out to the pokie pub later.

@OnionSoup Fair Dinkum!

Fascinating story! And yes, now I want a burger with fries.

When I was in Australia in the 1990’s, I found it interesting that they had Lonestar Steakhouse but had never heard of Outback Steakhouse. As you might suspect, the only “Outback” in Outback Steakhouse is in the marketing magic.

@goose08 The now-historic web comic User Friendly did an entire story arc about how the lead idiot in the organization made a right ass of himself on a trip to Oz, and the signature items from the Outback chain figured heavily in it.

What I know about Australia: They must all be standing upside down. Must make it messy to pee.

@phendrick Nah. This planet sucks just as hard in that direction.

All I know is that I had to make an emergency stop at a hungry jacks to use the toilet in Brisbane. It had nothing to do with the food since I hadn’t actually eaten there, but the association is unshakable

Jason, these have all been great posts! Please keep them going! I’m going to aim to collect a Meh for every Shoddy Goods to help keep them going! Sharing widely because they are so interesting & well-written! Thanks!

how does that ad copy say

“Open 7 Days a Week 'Till 1am – Sundays 11:45pm”

what does that even mean? are there 8 days in an Australian week?

is this a metric week?

@ekw Sounds more like 15 days a week.

Excellent story! Although that reference to dollaridoos was uncalled for. I’m so mad I’m going to call me member of parliament!

Candy in Australia is better than here. Exchanged American hot sauces for Australian candy with a friend. Even the same candy bar, Cadbury Dairy Milk, tastes different.

Also, Vegemite is awful except in a Cadbury Vegemite chocolate bar,

@callow Vegemite chocolate bar?!?!?

@Kyeh For real!

@callow So what does it taste like?!?

@Kyeh It was a long time ago and describing a unique taste is not something I am good at. All I remember is a little salty and a little something else.

From someone better with words: vegemite-chocolate-taste-test

LEGOS! EGGOS! STRATEGO! AWESOME!

@callow Thanks! Do you agree with the reviewer?

@Kyeh I thought it was better than vegemite alone or on toast but it’s not something I’m going to go out of my way to find. It was fun to try.

@callow I would try it too! I’m curious about most novel foods, except the ones that sound truly disgusting or dangerous (fugu fish, no thanks!)

How US-centric of Pillsbury to think that they should force a brand with 19 years of history to just change names when most Australians know nothing of that version of Burger King. I guess corporations gonna corporate.

Hopefully they didn’t have to have a creepy Hungry Jack to match that creepy ass Burger King mask.

@djslack Pillsbury has been out of the BK picture since sometime in the '80s. The current ownership-level control is by the same consortium that owns Tim Horton’s, and the current HQ is in Canada. And yeah, “The King” is creepy, and their ad slogans mostly suck. The most recent one, “You rule”, was made of fail as far as I was concerned. But their burger is decent, and the two-fer breakfast croissants are a better deal than the stuff at a lot of their competitors.