Bambi: The Space Between the Copyright Notes (Part 3)

15Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

In part 1 of this series, I untangled how Bambi, the novel by Felix Salten, made its way onto the screen as a Disney movie. Part 2 was a dive into Disney’s heavy reliance on licensed material, making it all the stranger the company would lobby for a 20-year extension to copyright. That extension led to Disney paying huge sums to the people, estates, and companies from which it licensed rights for some of its most popular properties. In part 3, we look at how Disney’s chain was fully yanked when it decided to countersue Bambi’s rightsholders, thinking itself rather clever.

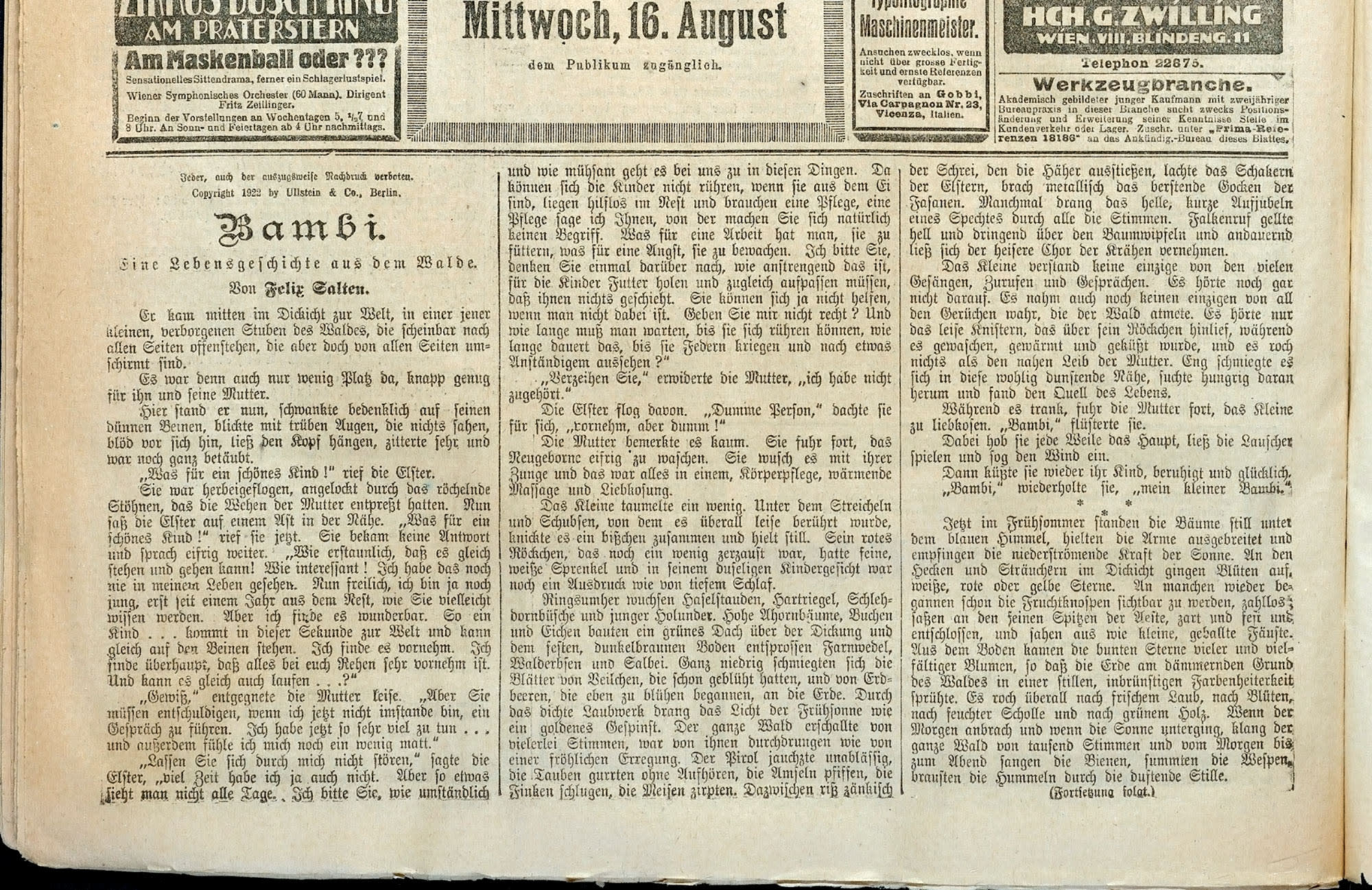

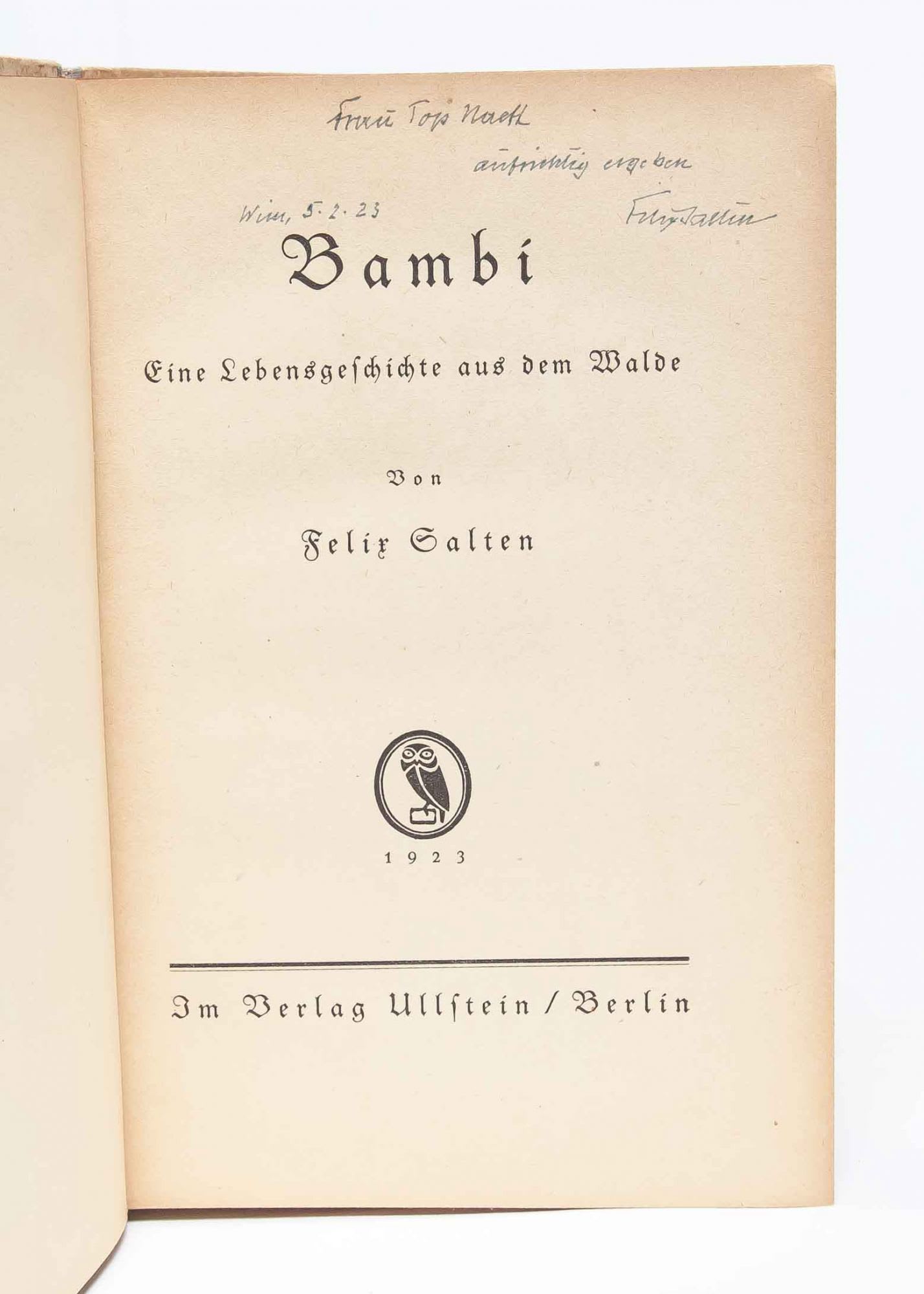

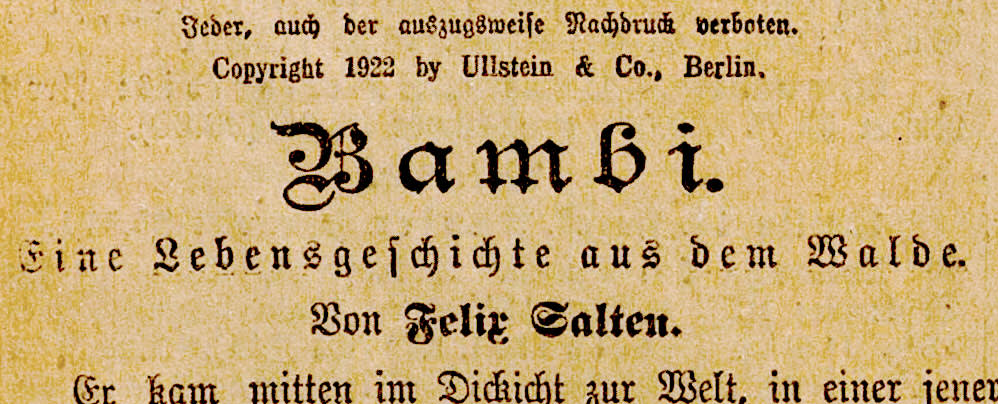

Felix Salten’s first edition of Bambi: A Story of Life in the Woods (Bambi: Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde) appeared in serial form in Vienna in the Neue Freie Presse (New Free Press) starting on August 15, 1922 and ending in October. Ullstein Verlag published it as a book in 1923 in Germany, and an edition appeared later, in 1926, in Austria.

When published in book form in 1923, no copyright notice appeared. That wasn’t unusual at the time, as no declaration was required in Germany. The 1926 version, however, may have recognized the lacuna—at least in Austria. The Austrian publisher of that edition added a separate notice that the book was published in 1926 under U.S. copyright.

The publisher also formally registered the copyright, sending in documentation to the U.S. Copyright Office. That requirement lasted until the 1980s when the U.S. adopted the Berne Convention rules that established copyright at the moment of creation. (Registration is now optional, but a copyright owner who files can claim treble statutory damages if they sue and prevail in a copyright-violation lawsuit.)

Salten’s wife, Ottilie Metzl, predeceased him in 1942. He died in 1945. His estate passed to his daughter, Anna, later Anna Wyler. Anna and her second husband, Veit Wyler (married in 1944), managed these rights through a renewal she filed in 1954 to extend the term 28 years and negotiations with Disney in 1958 over further rights and payments.

She died in 1977, and Veit Wyler and their two children, Judith Siano and Lea Wyler, sold the rights in turn in 1993 to Twin Books, a publishing house. (Wyler died in 2002. He was an incredible individual in his own right. Both children are still with us: Siano lives in Israel; Lea Wyler, in Massachusetts.)

Twin Books quickly set up a conflict with Disney, claiming the corporation had violated licensing terms agreed upon in 1958. The original filings seem unavailable—perhaps sealed. But the trial court’s decision in January 1995 notes, “Plaintiff alleges that last year it acquired certain rights in Bambi, and now seeks profits from the Bambi motion picture and an injunction prohibiting further exhibitions of the film.”

Disney’s response to the suit had a shocker: while it denied abrogating any deal, it said that the work had fallen out of copyright decades ago. Published in 1923, the company said that the copyright required timely renewal in 1951. Since it was not renewed, the work had, in actuality, been in the public domain since 1952. Ergo: Disney owed Twin Books diddly-squat.

While the trial court agreed in that 1995 decision that the renewal was invalid, an appeals court in 1996 reversed that decision and sent the case back for resolution. (Twin Books and Disney then settled out of court for unknown terms.)

The appeals court took the stance that the 1923 edition was not intended for distribution in the United States. Had someone published a version in America between 1923 and the 1926 copyrighted edition, Salter would have had no recourse! Because Germany had no copyright notice requirement, the work was protected in that country and established a proper publication record in 1926 in Austria. The appeals court wrote:

[Bambi]…was first published without a notice of copyright in a foreign language in a foreign country, and the general rule applicable to publications within this country does not necessarily apply.

This has left many experts livid over uncertainty.

First, copyrights gurus point out that this means there’s no certainty about the public-domain status of work published outside the U.S. that doesn’t have an explicit U.S. copyright notice. Even substantial research may not resolve the question; litigation may always be required if there’s a dispute.

You can see this in a 2009 appeals court decision about sculptures created between 1913 and 1917 in France by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. In 1973, the French Supreme Court determined some of those works had been co-created an assistant, Richard Guino. (Sculptures can be copyrighted! U.S. copyright law, in line with global conventions, allows protection of “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works.”)

The Renoir/Guino case is complicated, but it boils down to Guino descendents arguing Renoir descendents had violated an agreement over reproductions in 1982. Because the sculptures had never been copyrighted in the U.S., the reproductions were in unknown territory. A district court found, and the appeals court agreed, that with no U.S. copyright date, copyright had to be assumed to be in place 70 years after the death of Richard Guino. Guino died in 1973, so that means these works created before 1918 remain under protection until Dec. 31, 2043! The logic is tortured, but the appeals court found itself constrained. (I’ll get into a similar situation with a document written by John Adams in a later article.)

Second, the Bambi decision only formally applies in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which has jurisdiction over the western U.S. states plus Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Because the Supreme Court hasn’t taken up the matter, and no similar case has risen to the appeals level in other federal districts, the ruling isn’t binding elsewhere.

Third, it’s absolutely unclear to me whether the courts had access to the original serialized versions of Bambi since digitized versions of the Neue Freie Presse installments in Vienna absolutely show a copyright notice for Salten’s German publisher in 1922! In English and a Latin font, no less, instead of the gothic-style Fraktur used heavily in Germany through the point in the 1940s when the Nazis banned it.

Would that have changed the outcome since the work would have been affirmatively in the public domain because it had expired? Both 1922 plus 28 years (no renewal) or 1922 plus 56 years (with renewal) are still long before the lawsuit. Or did the German firm’s copyright assertion in Austria still not count under U.S. law? Picture my head shaking back and forth forever at this juncture.

The outcome may have left a legal complexity for years to come about certain valuable work that’s many decades old. But it was a positive one for the family, even though it had sold its rights. Salten and his heir had received only a fraction of the fees other authors and estates negotiated directly with Disney from the 1940s onward. We don’t know the terms with which the family sold Bambi’s right to Twin Books. Still, given how quickly the publishing firm sued, it’s plausible to speculate about additional payments based on Twin Books recovering money from Disney the family might have felt it was owed.

When Salten sold Bambi’s film rights, he was still a wildly successful journalist, novelist, and playwright, able to ply his trade, even though the dark storm was on its way. He may have been naive in selling director Sidney Franklin the rights for so little without prohibiting transfer to other parties or setting an end date for a film’s release. (Options sold today typically last for a set period of time. Some screenwriters have made a sad living selling script options that are renewed but never ultimately produced.)

His daughter and her husband and children fought for many years to obtain more compensation. The three non-public agreements made between Anna Wyler and Disney in 1958 ostensibly were more lucrative than anything previously agreed upon.

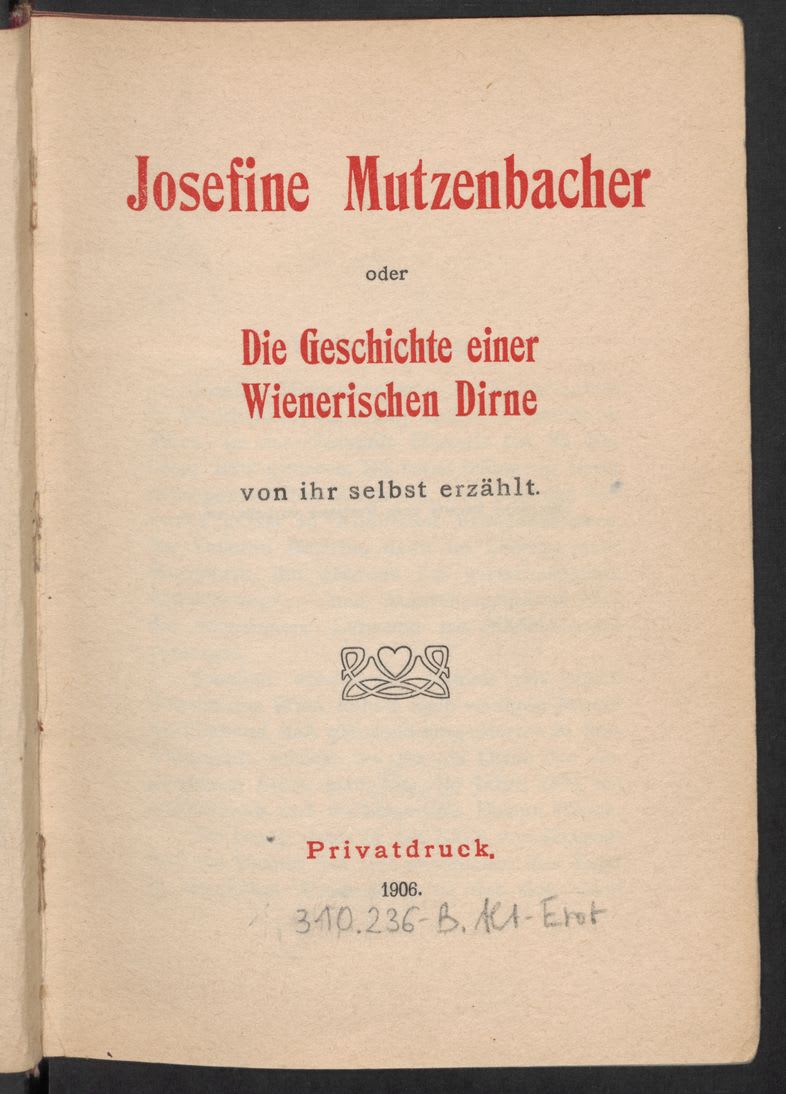

The estate also fought to untangle the rights for an incredibly pornographic novel published pseudonymously in 1906 in Vienna, Josephine Mutzenbacher or The Story of a Viennese Whore, as Told by Herself. It was thought Salten or his prolific playwriting contemporary, Arthur Schnitzler wrote the novel. In 1976, they tried to get royalties and halt distribution of a version of the book published in Germany, but were unable to find definitive proof Salten had written it; based on German copyright law, the work had entered the public domain.

Disney may have won one battle by getting the term of copyright extended another 20 years, but it also subtracted seemingly vast sums from its bottom line by adding two decades to all its licensing bills. If Disney hadn’t successfully lobbied to extend copyright duration, the original German version of Bambi in book form would have entered the public domain no later than January 1, 2002.

Now, it will finally emerge from its near-century of protection in 2022, at which point perhaps Disney will start pushing Bambi with unfettered abandon. The Simon & Schuster translation by Whittaker Chambers from 1928 lasts until 2024. The movie, copyrighted in 1942, will remain under an aegis through 2038.

In the part 4, the final part of this series, I circle back to the end of Salten’s life.

- 3 comments, 3 replies

- Comment

OTOH, make some merchandising deals, and it’s additional revenue.

@narfcake Only if the license holders allowed it!

@narfcake Less Boring. Moar flamethrower. Mel did it first.

This series is great. I can’t wait until the next episode.

@glennf Will you be doing other essays?

@yakkoTDI Yes! Monthly after this first four-part series. Thank you!

Just acquired…