Bambi: The Life of a Copyright in Disney’s Forest (Part 1)

37Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Hello, Meh folks! I’m back! Dave Rutledge asked me for more thrilling stories of obscure interest to tickle your fancy. I’ll be starting with some of the strangest twists and turns in copyright, involving Sherlock Holmes, John Adams, the movie Charade, Peter Pan, and James Bond. But first, into the woods…

What do a scandalous 1906 alleged memoir of a sex worker in Vienna, Alger Hiss, Nazis, Sonny Bono, and Walt Disney have in common? Bambi!

As with everything to do with Disney, it all comes back to copyright.

Over four weekly installments starting today, I’ll introduce you to the book by Felix Salten from which Disney adapted Bambi, the vagaries of copyright extensions that cost Disney plenty even while they reaped the rewards, the tangled copyright journey of Bambi and Salten’s family, and the final chapter in Salten’s life.

Humans may be cruel, but nature brutal

We all know the story of Bambi. It follows the life of a fawn as he makes friends (like the rabbit Thumper), falls in love (with Faline), encounters the cruelty of Man, witnesses his mother killed by a hunter, and has children and helps raise them. At least, that’s the Disney movie version. It’s funny and bittersweet but ultimately uplifting.

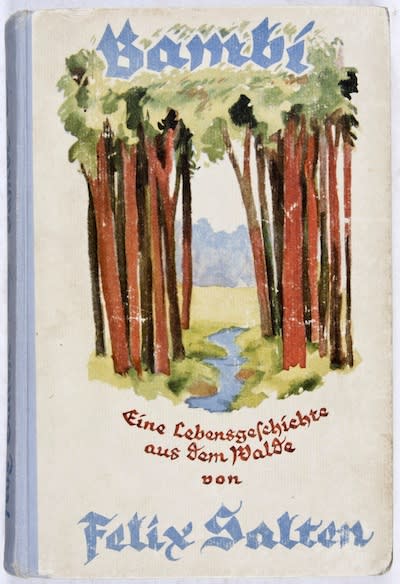

In the source story, it’s a far grimmer tale. The movie was adapted from a 1923 novel published in Germany, Bambi: A Story of Life in the Woods, written by the prolific Austrian journalist and novelist Felix Salten. In the novel, there are no chipper forest friends. As a fawn, Bambi doesn’t know his father, as adult male deer don’t stay with their offspring in Salten’s telling.

Bambi still has children with Faline (in the book, she’s his cousin) after entering a mating frenzy and fighting off other suitors, but then disappears from their lives as his father did. There’s a lot—a lot—more death. And it’s full of philosophical meditation. An entire chapter details the “thoughts” of two leaves nearing the end of their time on the tree, talking of death and the unknown. (Walt tried to animate this.)

Salten was a hunter, and his coming-of-age story was written for adults. It takes a bigger-picture look at the cycle of life in the forest and humanity’s interaction with it. It’s sometimes called the first “environmental” or “green” novel and taken as literal opposition to hunting and figurative opposition to fascism.

And, yet, the former wasn’t entirely Salten’s intent. Forest animals are absolutely brutal to other animals throughout his book, not just humans to animals. Bambi is treated harshly by the buck that he learns later in life is his father and becomes as hard-hearted as him, though that’s shown as natural rather than abusive. The book is perhaps more about the cruelty of nature—maybe even a bit nihilist in that standpoint—and our position as people relative to that cruelty.

(You can find Salten quoted in one German article and on a couple of websites as having said, “Bambi would never have been created had I not fired a bullet at a deer or elk’s head.” However, the few places that quote him in German and English translation offer no source for this statement, and I can find no record of it in any language.)

Fascism hadn’t yet swept Austria and Germany when Salten wrote Bambi in 1922, when it was initially serialized, though anti-Semitism was commonplace and institutionalized. (Salten, the grandson of an Orthodox rabbi, was Jewish and changed his name from Siegmund Salzmann.) The curator of an exhibition just this year celebrating Salten told The Times of Israel, “Salten himself never offered a commentary on the meaning of the book.”

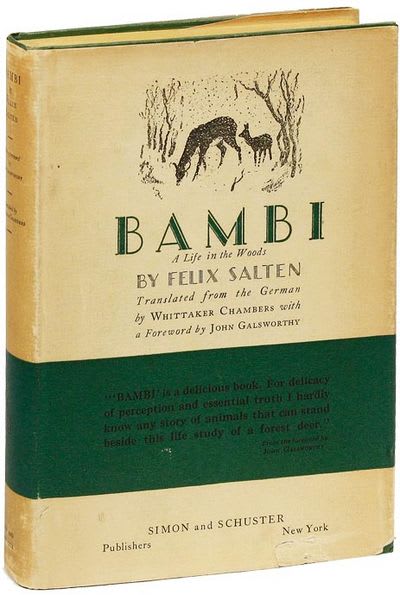

Neither movie nor book had a great initial reception. In Germany, where inflation raged, the book didn’t sell well; Salten later changed to an Austrian publisher and saw an uptick. When it appeared in English translation in 1928, however, it became a big hit. The translation was by Whittaker Chambers, by then already a member of the American Communist Party, and the man who would later be a key—and dubious—witness in the spy trial of Alger Hiss.

Chambers had taught himself German, had graduated Columbia just two years before under a cloud of disapproval over a play he wrote (called “blasphemous” by some), and Bambi was the first book he translated. The American publisher, Simon & Schuster, had been founded just four years before and bet big on mass-market sales.

The translation waters down the original’s transcendental bent and its frankness, which contributed to Bambi’s more concrete interpretation depicting animals and not avatars in the U.S. As Sabine Strümper-Krobb wrote in “‘I particularly recommend it to sportsmen,’ Bambi in America: The Rewriting of Felix Salten’s Bambi” in Austrian Studies in 2015:

…the English translation actually tones down Salten’s anthropomorphism in places and changes its focus in others, thus opening the possibility for the story to be understood less as a human story about persecution, expulsion or assimilation and more as an animal story conveying a strong message about the protection of animals and the necessity of conservation.

(Simon & Schuster, the book’s U.S. publisher since 1928, issued a new translation in 2019; the reviews aren’t great. A fresh translation of Bambi is due in January 2022—that date is convenient, as I explain later—from the Princeton University Press.)

However, Chambers’s translation was a hit. By the time Disney’s movie came out, the book had sold over 650,000 copies in the United States, partly as a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, according to newspaper accounts in 1942. Authors often received a tiny sum for those club sales, and, as Salten struggled financially in Austria and Switzerland, it’s unclear what proceeds he received.

Disney released the film Bambi in 1942 as World War II raged and the studio had no access to European markets. Salten hadn’t sold the rights directly to Disney, but to a director, Sidney Franklin. Franklin intended a live-action adaptation and paid Salten either $1,000 or $5,000 in 1933—surely a bargain, but not yet one of desperation. No one imagined an animation production given other work of the time. Franklin experimented with the film for years and finally sold the rights on to Disney in 1937 for a never-disclosed sum. Disney had a lot of peculiar ideas that led the studio down dead ends and some rather beautiful ones that never made it in, as with those leaves noted earlier.

The movie Bambi wasn’t exactly a bomb, but it performed short of the studio’s expectations at the box office. There was a war on, after all. Many reviewers and essayists gave it a negative reception because of its stronger twinge of anti-hunting sentiment than found in the original.

Bambi did become increasingly more popular each time it was re-released in movie theaters over the following decades. Pre-orders for its first home-video release in 1987 were for nearly 10 million copies. (Disney also produced two other Salten works: the live-action The Shaggy Dog, loosely derived from his 1923 novel, The Hound of Florence; and Perri, a fictionalized entry in a documentary series, from his 1938 The Younger Days of Perri the Squirrel.)

The novel and book’s greatest ultimate effect was likely akin to Babe, a movie that made many children into vegetarians—or at least kept bacon off their plate, even if Salten didn’t intend it. The death of Bambi’s mother in both the book and movie is a searing event for many adults, who remember it as a distinct moment in their childhoods.

As Robert Muth and Wesley Jamison write in Wildlife Society Bulletin in 2000, synthesizing a number of previous opinions:

Bambi gave voice to inchoate and diffuse values residing in a midcentury American society characterized by a profound sense of unease and anxiety. Although not deliberately designed as such, Bambi is perhaps the most effective piece of anti-hunting propaganda ever produced.

But no controversy over the story or its outcomes in any version in any country was as complicated and long-lasting as the history of its copyright. In the next part, I’ll explain how Disney built an elaborate self-kicking lawsuit that paid off for the ultimate owner of Bambi’s rights.

- 9 comments, 11 replies

- Comment

I get why they didn’t put talking leaves in the picture, but that segment was surprisingly moving.

@dave I guess it was too much of a thinker to drop into the middle of the film, but wow! I do appreciate that Walt dropped the plan to have several rabbits, each with their own names that corresponded to traits, like the Seven Dwarves.

Also in researching this story, I discovered in the original fairy tale as recorded by the Grimm brothers in their early 1800s book, Snow White (originally, “Little Snow White”) was poisoned by the apple on the evil stepmother’s third try, and that the prince didn’t kiss her—his servants dislodged a piece of apple while moving her to his castle. She revived through accidental Heimlich Maneuver.

@dave I also thought it was a very thoughtful talk between leaves. It should be a short on something one day, like the “lava you” short about the volcanoes. Very touching.

@dave Wow, so poignant…

Quite interesting. Looking forward to the next installment.

Can NOT eat venison or rabbit. Have many friends who do, but nope, not eating Bambi or Thumper.

The great Harry McCracken wrote about the building in which Bambi’s early production took place!

@glennf Oh, is that Phil’s brother? I know him!

Excellent write up. Modern copyright laws are all sorts of screwed up.

@yakkoTDI Yes, well. When Congress is always for sale, Disney gets to draft whatever copyright laws it can afford.

@cadmore @yakkoTDI

Disney was never interested in copyright for Bambi. It was always about extending the monopoly from the public commons to extract every possible shareholder dividend out of Steamboat Willie, aka Mickey.

@cadmore @mike808 @yakkoTDI See the next part! And much good it did Disney: they had to pay out huge sums to copyright holders they licensed from. They probably did make more money, but they also gave a lot away.

The trick is that when you license a work for a film, the film’s copyright starts ticking when it’s released. So if Disney hadn’t lobbied for the 20-year extension, Bambi would have remained under protection as a movie until 2018 (!!), while the underlying rights would have entered the public domain in 1999 or 2002, depending on whether copyright had been litigated at all.

While other companies could have released Bambi movies based on the original story, it’s unlikely they would have had the update the Disney Bambi did. Disney could have sold Bambi merchandise up the wazoo and done all sorts of new theatrical and DVD/Blu-Ray releases without paying an additional penny to the company that bought the rights from Salten’s heirs!

@cadmore @glennf @yakkoTDI

This is exactly what they did with all of their works, starting a new copyright clock on each new technological format release and sequels and anything related. Disney claims they were each a distinct, separate, and unique “derivative work” based on the original licensed and copyrighted work. However, each of the “derivative works” gets their own separate copyright clock.

That gives Disney leverage to sue anyone contemplating creating a similar “derivative work” based on the original work, even if it had entered the public domain. In short, they wouldn’t sue you for infringing upon the original copyrighted film release of Bambi, they would sue for infringing upon their BetaMax, LaserDisc, VHS, DVD, along with each region-specific DVD release, BluRay, region-specific BluRay release, and all of the permutations of each of those with or without “director’s cut” material, commentary, extended scenes, remastering, MP4-encoded with AAC stereo, MP4-encoded with Dolby 6.1 channel sound, H2.65 encoded versions for streaming, the version with subtitles, the version with multiple language tracks, and each deviation and variation of every format and content packaging.

And the strategy was made clear that Disney intended to sue you into oblivion by filing separate lawsuits for each separate work they allege you would be infringing upon the copyrights of.

Quite the chilling effect. Brings a tear (of joy) to my eye as a shareholder cashing in those dividend checks.

@cadmore @mike808 @yakkoTDI There are limits to that strategy—often the limits of the party being sued. But, for instance, when Steamboat Willie goes into the public domain on January 1, 1924, there will be a lot of copyright lawyers willing to defend anybody Disney sues illegitimately.

Note, too, that Simon & Schuster, faced with the copyright expiration on both Bambi and their Chambers’s translation of it into English in 2022 and 2024, released a new translation that has a fresh copyright on it—legitimately, but they have to contend in the marketplace. And the word is that the translation isn’t that great? So Princeton’s 2022 release of its translation of Bambi could become a new standard.

Have you read about the novel they based The Fox and the Hound on? Speaking of grim…

@The_Tim Geez, I feel depressed even just reading the plot synopsis.

/giphy books

Really interesting reading. I’ll be looking for the rest!

If it’s not obvious, Bambi was an important part of my childhood. Learning more of its history is something I look forward to.

Thanks for adding my font of obscure knowledge/trivia. Looking forward to the next installment.