Teenage factory starlets: Shoddy Goods 012

5

I’m Jason Toon and this is Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh telling stories about the stuff people make, buy, and sell. I’m on vacation so I’m mixing in some deep cuts from my own back pages along with the new stuff. Back in 2013, I saw a haunting old Soviet commercial and knew I must probe the fascinating mind behind it. Even I was surprised that I was actually able to track him down…

If advertising is the face of free-market consumerism, what does it look like when there’s no free market behind it? Pretty brilliant, judging by a remarkable surviving 1983 Soviet commercial for ground chicken.

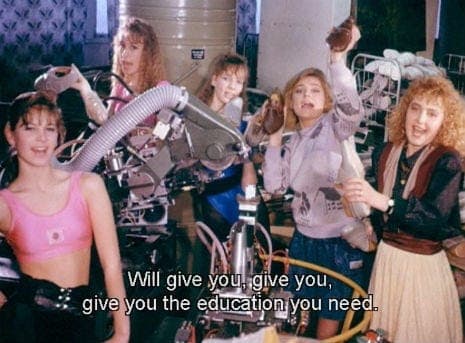

From 1979 to 1989, filmmaker Harry Egipt created dozens of surreal micro-masterpieces for the Estonian studio Eesti Reklaamfilm. Glamorous models vogueing with sheep, ecstatic paeans to collective-farm oranges, teenage factory starlets cavorting to unauthorized Rolling Stones tunes: Egipt’s commercials may have filled Western forms with Soviet ideological content, but their absurd, dramatic sensibility was wholly Egipt’s own.

Forgotten during Estonia’s post-Soviet collective amnesia, Egipt’s ads have since been seen by hundreds of thousands of YouTube viewers, sampled for the Borat movie, and now collected on a DVD available through Egipt’s website. I contacted Harry Egipt via email to find him alive and well in Estonia, with a lot to say about his work. (The numbers in the interview refer to the commercials on the DVD.)

Harry Egipt literally made mincemeat out of advertising cliches.

Shoddy Goods: What was the purpose of Soviet commercials, since the USSR did not have a consumer-oriented market with different brands competing for sales?

Harry Egipt: During Soviet times advertising had an entirely different purpose than it would have today. For example, it shows the absurdity of Soviet planned economy that the commercials produced by a state-funded agency were sometimes prevented from even being screened. The primary purpose of advertising was not to encourage people to consume, it was not to market a product or service, but rather to inform and educate people and shape their views on society in general as opposed to finding a market for a particular product. Advertisements were targeted at a wider audience, not at a specific group of consumers.

Soviet ads were absurdly twisted in the context of contemporary advertising compared to their capitalist counterparts. Selling a product was not as important as the entertainment value, thus making the ads themselves the product to be consumed. Products often vanished from the shelves without need for any advertising but ads were produced nonetheless. At other times an ad would be produced in hopes that, at the time of airing, a product would be available for sale. Quite often adverts provided a financial basis to make television programs – with less bureaucracy and more creative freedom. To this end my adverts possessed an artistic value and looked like music videos.

Shoddy Goods: Were you and the other creators aware of the element of absurdity involved in making ads for products that consumers could rarely buy, or that in some cases didn’t even exist?

Harry Egipt: Actually nearly all products or services that were advertised were more or less available. For example, oranges that were not grown in USSR were rarely sold on the market. But when a cargo ship was about to arrive to Tallinn (the capital of Estonia), the advertisement for oranges was aired on local TV (nr 47 “Oranges”).

Before 1983, advertising for the car Zaporozhets (nr 56) proved to be completely absurd in the context of Soviet culture (the car was only sold for a special purchase card). But in 1983 there was a unique economic turnaround in the Soviet Union and within a month the car was available with no restrictions.

My action was not to be bound by Soviet doctrine. My clips demonstrated that Soviet Estonians are not afraid of capitalist glamour like socialist glamour (nr 82 “Luxury Goods”, nr 40 “Baked Apple in Pastry”, nr 78 “Perfume Plot”), nor young and beautiful dancing girls (nr 24 “Kalev Chocolates Selection”) nor other beautiful naked girls (nr 64 “Mistra Carpets” and nr 28 “Floare Carpets”).

It’s totally normal in Estonia to take your sheep shopping with you. I assume.

Shoddy Goods: Were you familiar with Western TV commercials at the time?

Harry Egipt: Since 1970s we could see TV transmissions from Finland in the northern part of Estonia and this was our window to the western world.

Shoddy Goods: You worked for Peedu Ojamaa, the formidable advertising pioneer whose studio Eesti Reklaamfilm essentially invented the Soviet TV commercial. How did you come to work for him, and what was he like to work with?

Harry Egipt: Actually I have no formal education in marketing or film making. After I finished my history studies at the university in 1972, I started to work as a light technician and later became a cameraman in our only local TV broadcasting station, Estonian TV (Eesti TV). In 1979 Peedu Ojamaa made me an offer to come to work for the Estonian Commercial Film Producers (Eesti Reklaamfilm). I started as a director and pretty soon started to write scripts as well.

A documentary film titled Goldspinners gives a good overview of how Peedu Ojamaa managed to build up Eesti Reklaamfilm.

Shoddy Goods: What was the creative process like at Eesti Reklaamfilm? How much autonomy did you have in making your commercials? What role did the “client” play in the process?

Harry Egipt: A customer would come to the office of Eesti Reklaamfilm and told us about the product or service they needed a commercial for. After a time schedule and a budget were agreed upon, the order ended up on my table. From here, I created an idea, did the casting, handpicked the crew, directed and produced the ad.

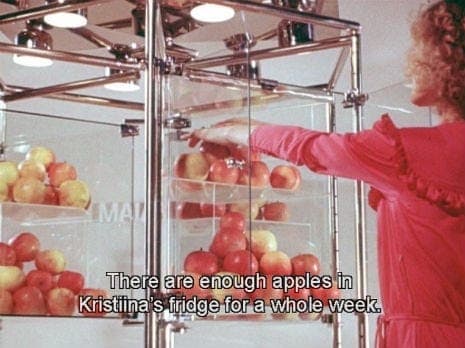

Or, y’know, the rest of her life.

In general, my film projects can be considered as a one-man show since I was the author, director and producer. My work is characterized by an utterly unique style, which uses innovative ideas, fast editing, original music and gorgeous models. My ads were different from other directors and copywriters who worked for Eesti Reklaamfilm. As customer and audience feedback was very positive and clients trusted my solutions, Eesti Reklaamfilm gave me the liberty to fulfill my ideas and rarely challenged my concepts.

Shoddy Goods: The music in your most famous commercial, for chicken mince, is the most ominous and discordant I’ve ever heard in a TV commercial. Combined with the images of the mince coming out of the grinder, the chickens, and the models, the effect is deeply disturbing. Was this your intention? Were you hiding some kind of commentary in this ad for processed chicken?

Harry Egipt: The Chicken Meat Poultry Factory had at that time bought new and very modern equipment for their factory for making minced meat. They asked me to make a commercial where the whole process could be seen – how the chicken was put in the grinder with feathers and bones and how the machine was able to separate the meat from the leftovers. As not to upset a lot of children and animal activists, I managed to reach to a compromise so that only the final part, where the minced meat was coming out of the grinder, was shown. A famous Estonian composer, Alo Mattiisen, at that time created the music after he had seen the edited material.

Shoddy Goods: Did you ever do any political propaganda work?

Harry Egipt: No, never.

Shoddy Goods: Did you ever feel pressure to do so?

Harry Egipt: No. In Soviet times advertising existed only in the form of propaganda. Propaganda was made to glorify the Soviet way of life. The most prominent was of course political propaganda for the unopposed Communist party. Commercial advertising was nothing more than propaganda for commodity goods like my ads nr 4 “Lemon” and nr 5 “Green Onions”.

Shoddy Goods: How did the end of the Soviet Union affect your career? Have you continued to work in advertising?

Harry Egipt: Unfortunately Peedu Ojamaa was not able to keep abreast of the times and could not cope with the new market economy. After Estonia regained independence in 1991, many employees left the company and started their own businesses and so Eesti Reklaamfilm was disbanded.

Since then I have independently produced some TV commercials for my son Hanno – you can see them on the DVD (nr 84 “ThermiSol Rock’n’ Roll” and nr 53 “Serla Household Paper Towels”). I have also directed and produced some ads after the DVD was issued (“Don’t Smoke, Lung Cancer Kills and Early Detection of Skin Cancer Can Save Lives”). I would still very much like to do commercials, but times have changed and in Estonia a younger generation is running the show and has different ideas.

Shoddy Goods: Are you surprised that your Soviet TV-commercial work has found a new audience in the West?

Harry Egipt: This is a big surprise, if it is really so.

Shoddy Goods: What can today’s advertising creators learn from your work?

Harry Egipt: Creativeness, advertising as an art, how to create memorable ads that viewers do not tire of, and how to produce innovative masterpieces on a limited budget.

To the tune of “Honky Tonk Women”. Not a joke.

- 6 comments, 2 replies

- Comment

About zero. Also I’m still in denial that the 80s was 40 years ago.

Yes.

i know nothing comrade.

if this person is good party member, then i wish to hear from them. if they are not, well, we know what needs to be done.

Is there one for Минский тракторный завод?

Minsk Tractor Plant according to the translate function in firefox

I don’t know how much could be discovered about it, but I’d be curious to know the background behind Isuzu’s failed effort to market their cars in the US. They had one of the more unique ad campaigns with Joe Isuzu, but I always wondered whether it wasn’t unintentionally designed to fail. Sometimes an ad doesn’t convey the message that the advertiser wanted to deliver. (Several people have made YouTube careers of lampooning examples found on FB Marketplace and elsewhere.)

@werehatrack They didn’t have the same amount of cash flow R&D, so their vehicles were always “a few years behind” the competition. The Isuzu P’up was the last mainstream passenger vehicle offered in the US to still be carbureted. In 1994.

For perspectives, even the Yugo got fuel injection in 1990.

They did ride the SUV craze of the late 90s/early aughts, but as competition increased, there was no compelling reason for their products versus that from another manufacturer.

For more consumer reporting that will be completely unhelpful when shopping for a new vacuum cleaner, waste some time with these Shoddy Goods past:

Those totally unhinged Quiznos commercials with the freakish stuffed animal things.