Nothing is lacking: the long history of intentionally blank pages

37You’ve seen this phrase your entire adult life, in manuals, in PDFs, and, if you’re a real wonk, in budget reports and financial documents: “this page intentionally left blank” or a variant thereof. It’s ironic, as it’s literally false, a kind of Cretan’s paradox of document production or perhaps a Magritte-inspired goof.

It makes a certain sense in printed documents, where an entirely blank page could leave the reader wondering if something should be printed on it. In a PDF, it just seems wrong, except that PDFs are often produced from the same source and process as print documents.

I thought the phrase might trace to the late 1800s, after hot-metal typesetting allowed much more rapid progression from manuscript to print, with less planning and oversight than previous handset type. Noting a blank page as such could have reassured readers of certain kinds of documents, especially financial reports.

The phrase, though, is far older than I suspected. We have to roll back further to the very dawn of movable-type printing in the Western world, when a version first appears in Latin. By the 1920s, the phrase starts to appear regularly in accounting and financial documents—possibly due to the innovations in production I mention above. In more recent decades, it spread to manuals, perhaps because of the literal-mindedness of many of us geeks.

Blanking out

A blank page is a waste and an affront, and after fielding enough queries about the apparent mistake, a manufacturer might want to add a notice. But why have a blank page at all? Partly because printers assemble books from larger sheets of paper, which are folded to the desired book size, and the remaining edges cut to open the book pages. This remains as true in modern book production as when all books were written by hand.

For manuscripts, these folded sheets are called quires, folded and cut before being scribed. The advent of movable type in Europe allowed printing a large sheet with multiple pages, called a signature. The Gutenberg bible used a folio as its signature size, which is two pages printed on each side and then folded without cutting. Signatures in early printing were typically 2, 4, 8, 12, or 16 pages per side.

Proper planning for manuscript scribes dating to the earliest books assembled from quires and to the earliest days of European printing could prevent blank pages at the ends of quires and signatures. But sometimes bad estimates, reprinting, or mere aesthetics intervened.

There’s a historical propensity to start new chapters and other book divisions on the right side (the recto) rather than the left (the verso), maybe because of signature assembly, but possibly because left has long had a general negative association in Europe and elsewhere: maladroit (“bad” plus “right,” as in the direction), gauche (literally, “left”), and so on. There’s no definitive account, however.

None shall paste

I went deep in Google Books and other online sources to track down the origin of the blank-page phrase. Google Books has some red herrings where it or a third party inserted a version of the phrase to confirm no scanning error had occurred. Books dating back hundreds of years describe even older volumes with references to blank sheets, in this case helping a buyer or librarian ensure that a given copy of a book is complete.

That only got me so far. I turned to experts in the history of the book and the history of business, many of whom were stumped about this particular piece of trivia. But Sarah Werner was a wellspring of knowledge. She’s a book historian, formerly of the Folger Shakespeare Library and currently investigating how early books were made.

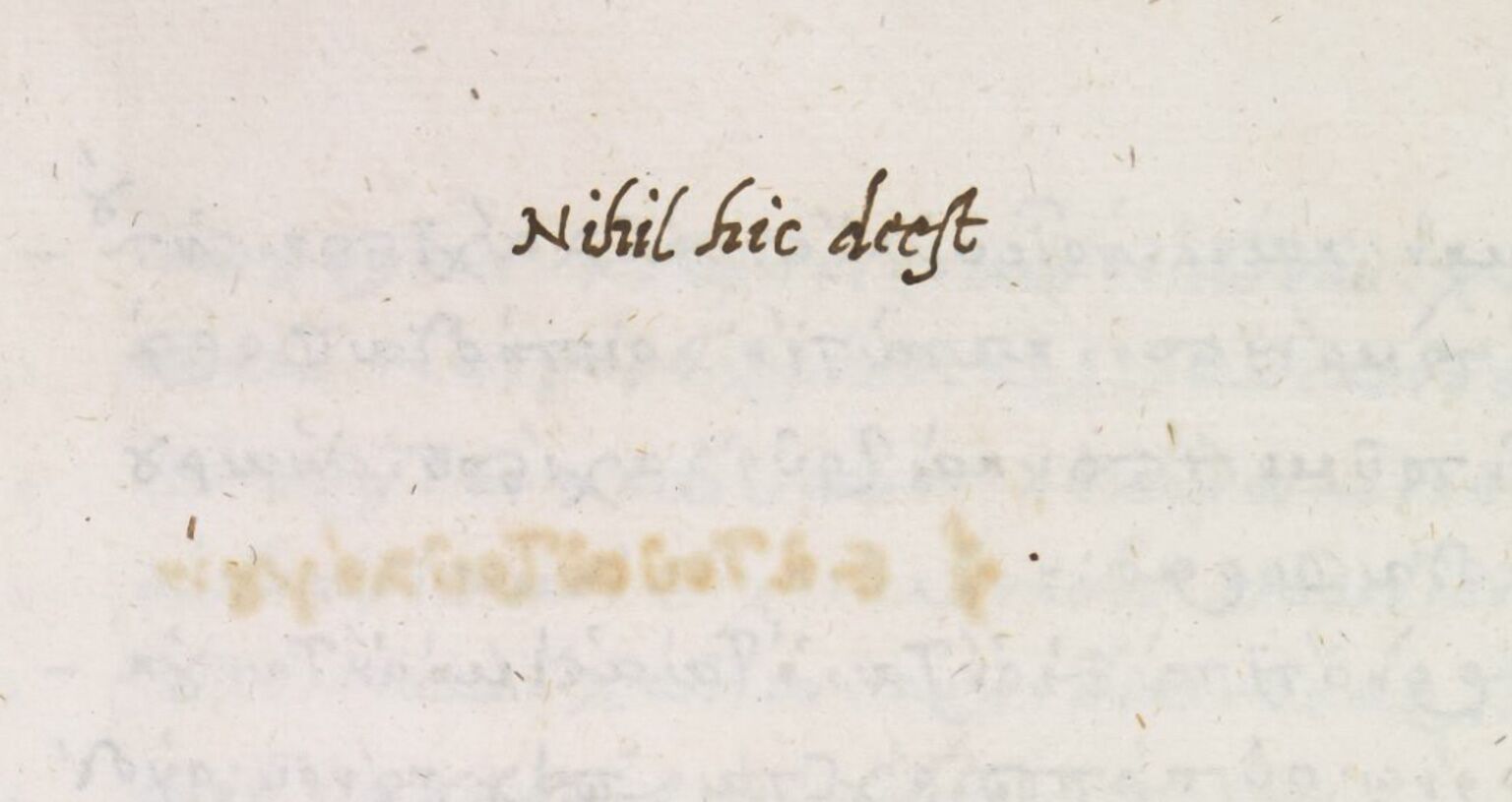

She’d found a 1541 manuscript, “Justin Martyr, Opera,” in which on a blank sheet a different hand (Werner thinks a later reader) wrote “Nihil hic deest”—roughly translated, “Nothing is lacking.” Variants appear on later pages.

Werner says she thinks “the original scribe left it blank because his copytext didn’t have that bit, and maybe he was going to go back and fill it in, and so guessed the amount of space it would take and left that blank.” Other empty pages weren’t so noted, however.

For a manuscript, scribes could work in concert. Werner explains:

You’d take a stack of leaves and fold them and then write. When the quire was full, you’d move onto the next one. From a writing standpoint, it makes sense that it’s easier to write on a small gathering of leaves than in an already-bound codex. From a production standpoint, it means that the volume does not need to be written in sequence; multiple sections could be copied simultaneously…

But Werner also put me on to an even older reference via a tweet she’d seen recently. Joe Howley, an assistant professor of Latin literature at Columbia University, had posted a picture from a 1471 book that he was examining at the University of Pennsylvania.

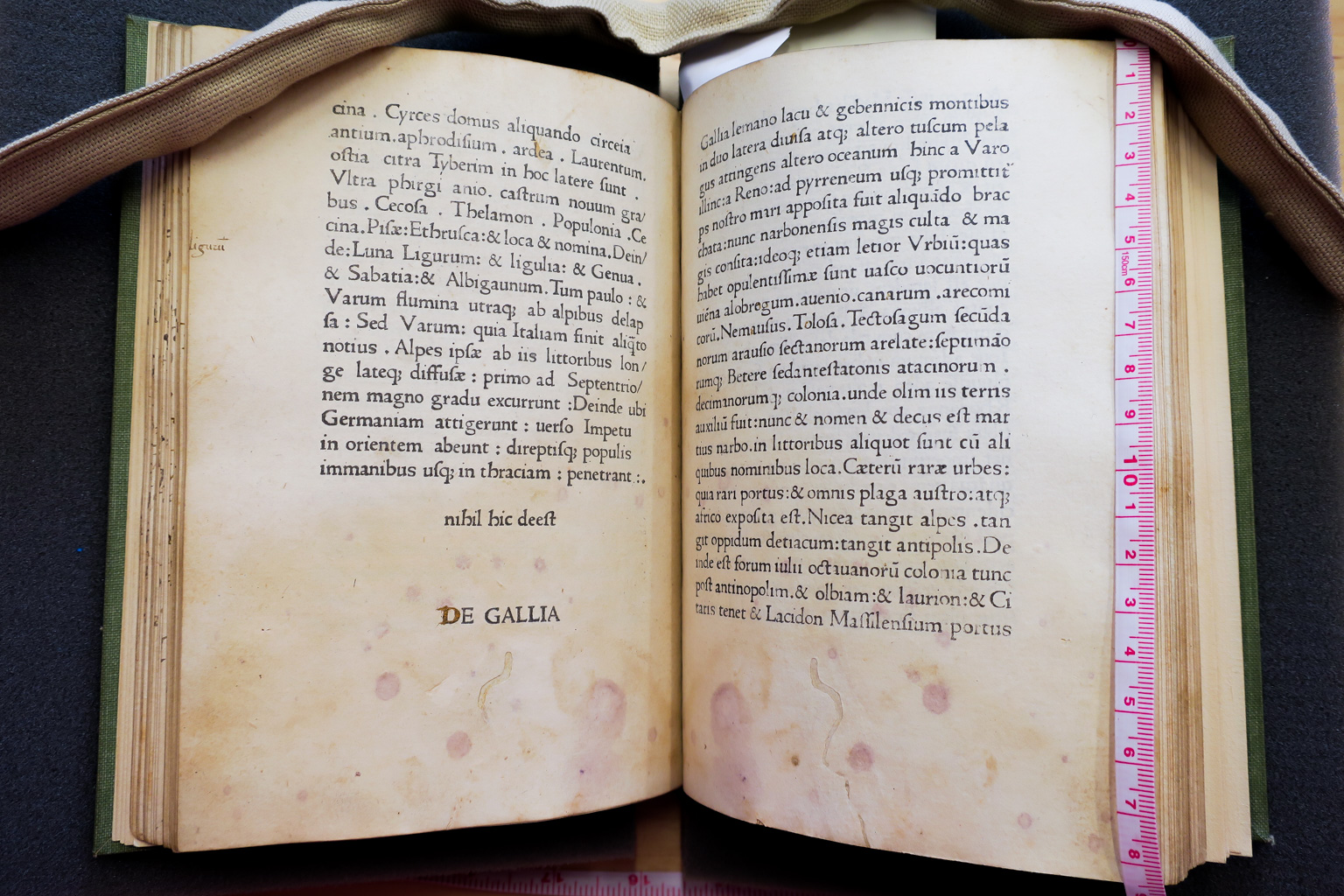

At the bottom of a page in Chorographia of Pomponius Mela, a work written 1400 years prior in Rome, appeared our friend, “nihil hic deest,” below a few lines of empty space. Below that phrase is the heading (“De Gallia”) that ostensibly should have been at the head of the next page.

Design standards in this era, known as the incunabula (“in the cradle”), were still in flux, as printers figured out what features of manuscripts to carry over. Howley notes that in this edition of Mela, some section heads appear with blank lines above and below, while others are crammed into a line. “These printers don’t really have a consistent house style when it comes to printing headings of sections,” he says.

On this page, he says, “Something happened where the layout they were stuck with—with the text and the header—that it generated just enough white space, they were worried that it would look like something was missing.” Many books of this era filled out a page completely from top to bottom, unless an error was made.

A few other copies of Mela from later periods have been digitized, but they were typeset anew, and don’t include that text or the heading issue. This page-ending oddity was known, as it appears in a description of the book in an 1812 bibliography of volumes in the collection of George Earl John Spencer, one of Lady Diana’s direct ancestors.

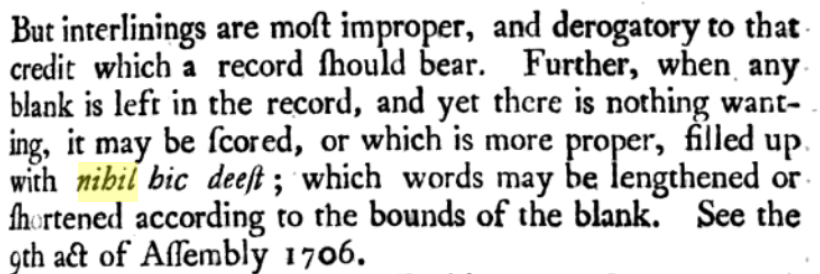

Though this use of the phrase appears to be relying on a convention that would have been familiar to readers, centuries pass before the historical records shows a reference to anything similar. A Church of Scotland book (1873) of numbing detail about church operations notes that “nihil hic deest” should appear to indicate that a roster is complete.

There’s a gap once again to the 1920s, when we start to see our old friend, “This page is intentionally left blank” in various forms in English. (If there’s a convention in other languages, I was unable to find it.) The excitingly named Tentative Scales of Class Rates and Distances Between Common Points in Truck Line Territory (1922) is the earliest reference I can find in that period. It occurs again in the Fletcher Cyclopedia of the Law of Corporations (1931) and Railway Accounting Rules (1937). The Traffic World trade magazine notes in 1932 the use of the phrase in another document. There must be many, many more appearances given the ordinariness of these venues, but so far they’re lost in digital wastelands.

I’ve walked into the past as far as the current accessible record goes, but I’m positive having peered so far back that the practice precedes the 1471 book Howley found it in. New phrases can appear out of nowhere (de novo!), but the fact that it was used decades apart in two different methods of book production make me believe this hardy survivor into the 21st century has deeper roots into the past.

Peering into the margins

This topic was suggested by a Meh.com forum member, and I’m delighted how deep the rabbit hole went down. Everything, no matter how trivial, has a history that weaves its way through old habits and new forms. When is a blank page not a blank page? When it announces itself as such in any era.

- 19 comments, 38 replies

- Comment

@carl669

@carl669

[This fucking page intentionally left motherfucking blank.]

@glennf

@carl669

All those who have ever used “this page intentially left blank” or similar have committed plagiarism and violated my copyright.

/giphy novelist

For context:

I would reply, but this margin isn’t long enough for the full proof.

@glennf

Yes it is!

[This page intentionally left blank.]

@f00l

@glennf

Yes, the full proof is an exact fit.

I esp like the lovely font and the full edge-to-edge formatting.

This Space Intentionally Left Blank for President!

“Nothing is lacking”

in this best of all possible worlds.

@f00l

OK, everyone, just go ahead and ignore me.

/giphy best of all possible worlds

@f00l

/giphy best of all possible whorls

@f00l

/giphy intentionally left blank

@f00l

/giphy Leibniz

@carl669

/giphy done

@f00l

/giphy Voltaire

@f00l

/giphy Candide

@f00l

/giphy Dr Pangloss

@f00l Sure that’s not Bezos?

@LaVikinga

The Bezos has always been with us. It has appeared over the Millennia with so many names and so many faces.

@f00l I think that condom gif is so you can intentionally shoot blanks…

I always put “This page accidentally left blank” on the blank pages in my TPS reports.

@PocketBrain I wish I came across one of those every once and a while.

/giphy specifications hurt my brain

@glennf Once again, a fascinating post!

@dashcloud The little footnotes in life are the best. Thank you!

The reason given to us in reference to the phrase “this page intentionally left blank” in military publications was to leave extra room for future revisions. The theory behind it being that as long as the page count stayed the same, the entire publication did not require review before reprinting, just the revised portions. Food for thought.

@cobracat03 I’ve seen equipment manuals from Evertz do that; they come in 3 ring binders and if there’s ever an update the blank pages can be replaced while keeping page numbering the same.

@jqubed So like the reason that the convention was to number BASIC lines in tens?

Many years ago I pondered the very statement that is under discussion here in this most illuminating forum. This is what I came up with: http://parodyman.com/writings/Blank.htm

This was a great read, but why was it given the Broadcast status? And was this originally written for a blog out or something that I can subscribe to?

@jqubed See the introductory paragraph of Glenn’s first post here.

@jqubed We might add a note on subsequent pieces; good thought.

@brhfl Ah, that clears it up.

@glennf Yes, that would be good; highlight that this is a feature of the website and not just some random user getting his unusually-in-depth-work-for-a-forum highlighted, and include links to your website/Twitter so we can get more!

Next broadcast:

The origin of the term TL;DR.

/image TL;DR

@jsh139 I’m not certain, but I think it had something to do with @marklog

@curtise wow, now I own all of tl;dr!?

@marklog yes.

@marklog Dog-gone right you do!

@marklog Nice to see you around again.

@jsh139 This is my favorite, though it is rarely seen:

Ceci n’est pas une commentaire.

@beavsco

Oh yeah? And what if I roll it up and smoke it?

Die beste aller möglichen Welten

@f00l Newton rules, Leibnitz drools!

Esse est percipi.

@beavsco

They both completely Rock and Rule.

And Leibniz’s conceptual notation was far superior to Newton’s - to the degree that English mathematicians using Newtonian notation fell far behind continental mathematicians who followed Leibniz’s practices.

–

I see that I have been perceived. I suppose I must have existed. Possibly.

As were you, and did you, elegantly. In tribute, I respond, with humilité:

“Ceci n’est pas une commentaire”

I actually have no pipe - or “pipe” - with which to smoke that.

Veni, Vidi, Salutavit.

@glennf The Internet Archive is testing a search-inside-the-books feature, so maybe you can extend your search there.

@glennf

All my insanity and riffing aside, your soon-to-be Five Easy Pieces plus-i-hope-many-more-articles-on-the-way-asap are beyond wonderful. I read them all, several times - first, for the jokes and riffs; later for actual depth of content, assuming I’m up to it; finally, and multiple times, in, I hope, deep appreciation.

I am envious of the skill and dedication used to gather the background, and the grace and gravity of the final written result. I wish I could write thus. Ahhh, my prose is earthbound.

Please give us more. And then more. And then…

Die beste aller möglichen Welten

@f00l

Post-The-Fuck-Script:

I would dearly like it if all your articles had their own link, or tab, or whatever apart from search, to make this continuing trace of intelligence obvious to newbies and other addicts of this fools’ paradise.

Post-Post-The-Fuck-Script:

Books? E-books? Audiobooks? Articles? Musings? What else of yours is out there, please? Or if not to be given links to yours, I’ll take a few of your favs. Please. I could use a little Quality now and then.

@glennf Thank you! I’ve often wondered about the phrase and why it seemed to be only occasionally necessary.

The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt. I think you might enjoy it. I stumbled across it in audio form so “read” it the lazy way. Don’t think I’ll ever look at an ancient book without wondering if it’s not hiding greatness.

@LaVikinga

Thx for book rec! How about:

"All That is Solid Melts Into Air:

The Experience of Modernity"

Marshall Berman, 1982

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_That_Is_Solid_Melts_into_Air

@f00l From its description alone, I see I’ll have to unearth my “school brain” as well as do quite a bit of homework. Baudelaire, Pushkin, AND Dostoyevsky? Nothing like some light reading for late summer afternoons. I’d be in way over my head without doing quite a bit of background reading.

@LaVikinga

Turns out The Serve was already in my Audible library.

As soon as I am finished with a few other tasks, it gets a

/giphy bump

@f00l Ouch!

I truly liked having the audio version (with Edoardo Ballerini–he was in Boardwalk Empire with Steve Buscemi).

Although I can pronounce Spanish, my Italian is atrocious ( and my French, well, we shall not speak of the tragedy that is my attempts with the French language).

“Oh. THAT’S how you pronounce it??? Yeah, I wasn’t even close.” I am the ugly American.

@LaVikinga

You aren’t alone; I am with you as The Ugly American. I can read/understand/speak a teeny weeny portion of German, French, and Spanish. Not even sure about the counting to 10 part.

And to think my aunt was a Fulbright scholar so fluent in all those, plus several more, that native speakers did not realize she was not one.

(Worthless excuse: “Well, they all speak “American” anyway, don’t they?”)

/giphy hangs head

More from Joseph Howley: a 1584 example of filling a page with “lorem ipsum” style text!!

Some more scholarship from Dr. Howley:

@glennf The page says to a binder that it’s not needed and should be removed. Most binders did! But it’s still extant in a few copies.