Housewives in revolt: Shoddy Goods 053

5

Seems like Dads are always grumbling about something - but when Mom’s had enough, you know it’s serious. Hi, I’m Jason Toon. In this Shoddy Goods, the newsletter from Meh about consumer culture, I look at the moment when fed up moms, wives, and grandmas put inflation anger on the political map.

[note from Dave: I flubbed the Shoddy Goods chat link last week, so if you’d like to join with others in Woot memories, here’s the chat thread that’s still going strong.]

It was a jar of olives that broke the camel’s back. A 52-year-old grandmother named Rose West cornered a supermarket manager to ask him why the price of olives had gone up four times in a month. His response, she said later, was “stick to your cooking and let us decide prices.”

So in October, 1966, dozens, then hundreds, then some 100,000 women in Denver began boycotting the five major chains that controlled a total of 150 stores in the area. They were hardly '60s revolutionaries, let alone feminists. They called themselves housewives. Many of them went by their husband’s names: Rose was often called Mrs. Paul West in the media.

But they were no shrinking violets. For a few months, they made national news and rattled the supermarket chains from coast to coast, in an early stirring of the consumer movement that would explode over the next decade.

Come on down! Some Raleigh, NC housewives stage their own showcase showdown

“We don’t like to feel we’re being taken to the cleaners and we’re tired of hearing about some rich, invisible middleman who is causing prices to go up," said Mrs. Jay S. Threlkeld (husband’s name again) of Housewives for Lower Food Prices. "We’re going to shop at independent and neighborhood groceries until we convince the chains we mean business.”

“The gals are waking up”

Organizers took credit for a subsequent grocery price war in Denver, claiming some chains dropped prices by 20%. In the midst of the '60s upheaval, the press found the man-bites-dog aspect of the protests irresistible. Housewives protesting, ha ha! But patronizing coverage is still coverage. Inspired by West’s boycott, picket lines formed around supermarkets from coast to coast.

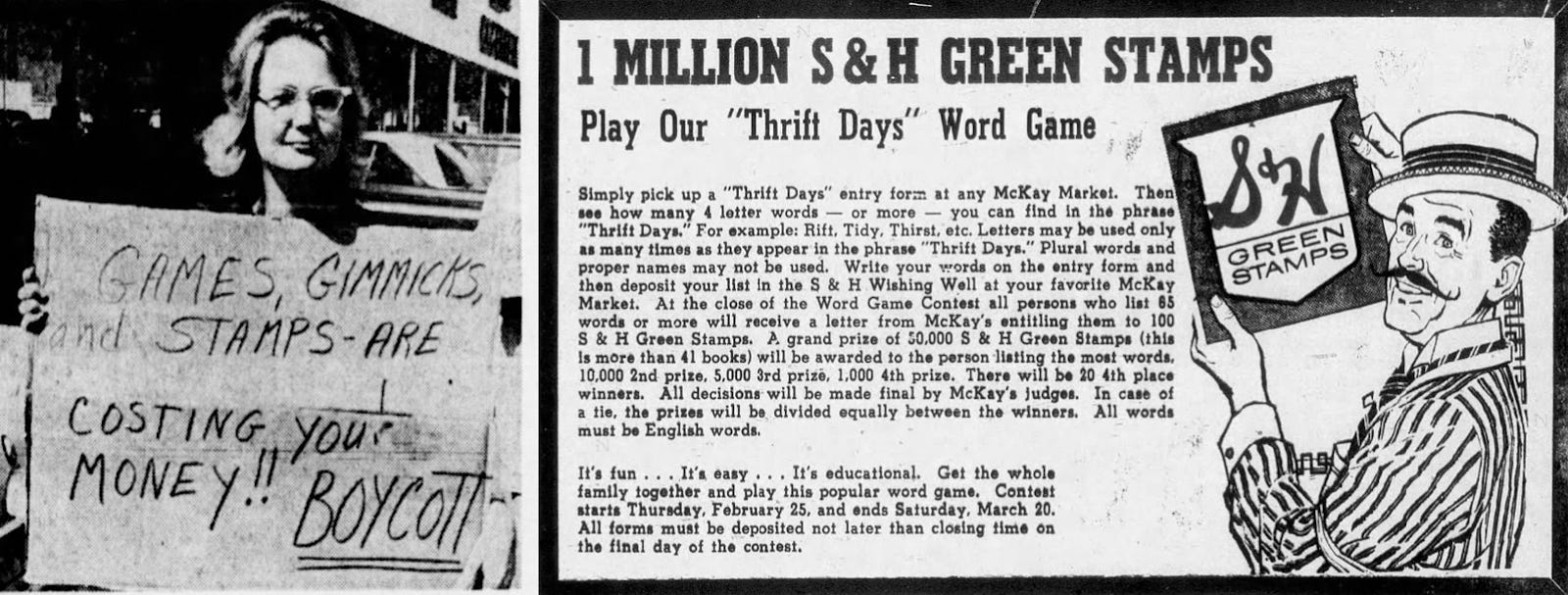

One particular target of their ire was the various trading-stamps and sweepstakes programs that were so ubiquitous at the time. Rather than spend money on promoting these gimmicks and awarding prizes, the protestors said, why not lower prices for everyone? (The industry later admitted that the costs of these loyalty programs added about 2% to retail prices.)

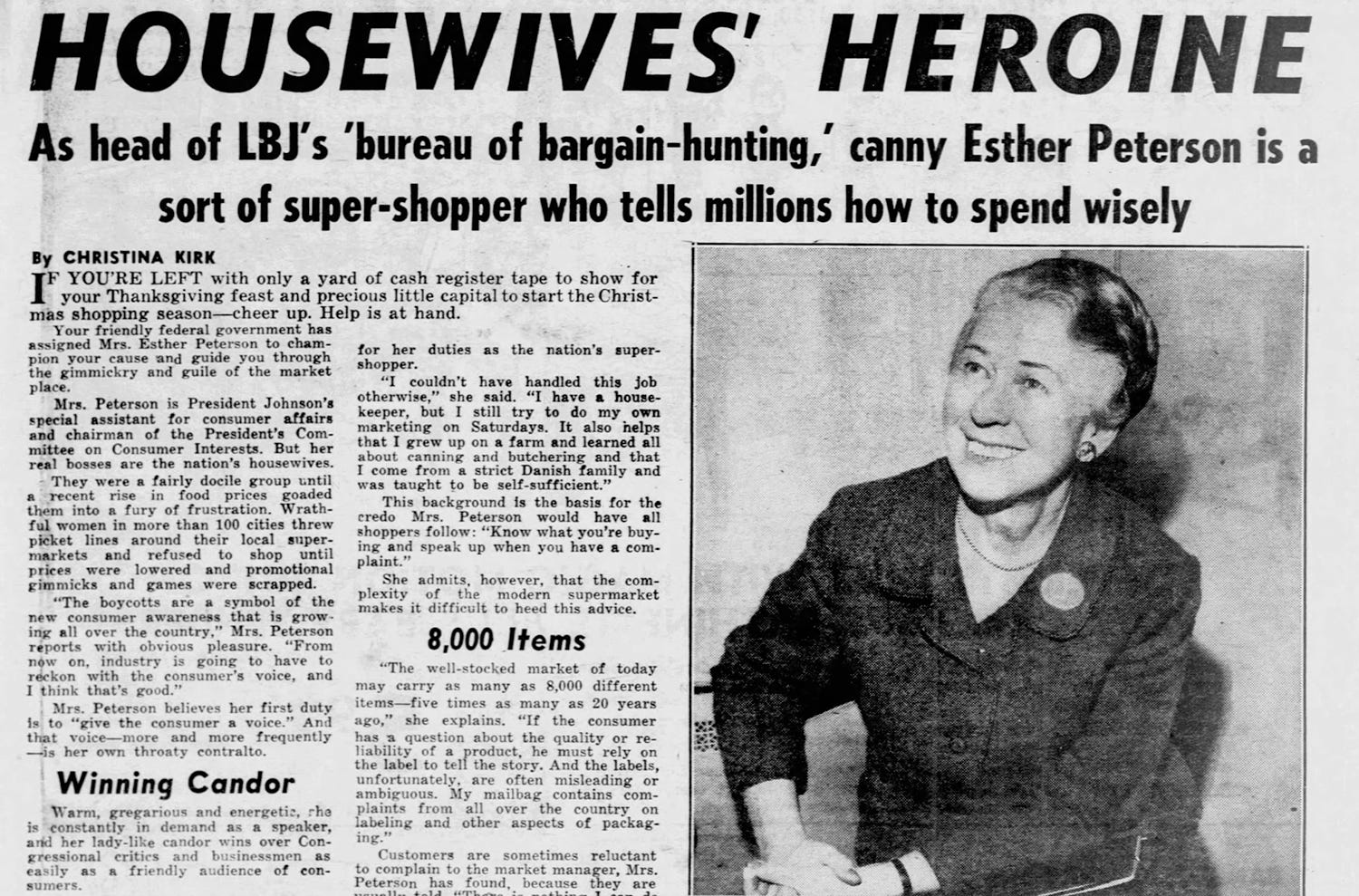

The protestors found a friend in high places. Esther Peterson had been appointed as a Special Assistant for Consumer Affairs by President Lyndon Johnson. A former union official and Assistant Secretary of Labor, Peterson’s sympathies were firmly on the side of the housewives. She was invited to meet with the Denver group - “Because we think we can trust you,” one leader said - and gave them hugs in front of the press.

“I just think it’s so beautiful that the gals are waking up,” Peterson said. “From now on, industry is going to have to reckon with the consumer’s voice, and I think that’s good.”

You go, gals, Esther’s got your back

The supermarket industry fumed that they were being scapegoated for factors out of their control. It’s true that grocery was, and is, an extremely low-margin business, highly sensitive to upstream cost increases. Supermarket profit margins usually cited in reports at the time range from 1% to 1.25%, or about a penny on every dollar of sales.

But the Federal Trade Commission did find that the steep increases in retail bread and milk prices were two to three times higher than the increases in raw ingredient prices. “Retailers not only passed on the increase but added to it by expanding their own margins, both absolutely and proportionately,” their report concluded.

Or, as Tulsa housewife Mrs. W.B. Gillespey of Citizens for Lower Prices put it, “Somebody between that milk cow and when we buy it is sure raking in the money - and it’s not the farmer.”

If the grand poobahs of grocery did have a case to make for the multifaceted complexity of inflation, they made it in the most condescending way possible.

Calm down, ladies

“The housewife is wrong,” Campbell Soup President W.B. Murphy told Time magazine. “The food store is a handy goat.”

“The housewives are emotional,” harrumphed an unnamed executive in the pages of Life. “The logic of our balance sheet does not interest them.”

The protestors “are not interested in the facts,” said Dan Bell of the Denver Better Business Bureau. “They just want the price of bacon reduced.”

“Maybe they need a recipe instead of a picket line,” another exec sneered.

Somehow this line of argument proved less than persuasive. A survey of protestors found that 76% blamed high prices on profiteering middlemen and 68% blamed supermarkets, while just 18% blamed high wages for industry workers and 5% blamed farmers. (The highest number, 88%, blamed supermarket advertising expenditures, consistent with the heavy anti-“stamps and games” message of the protests.)

“Guess I’ll have to go back to the barbershop quartet”

The Johnson administration started getting nervous, to Esther Peterson’s detriment. She would be sidelined and then eased out in early 1967. “President Johnson’s consumer initiative had been partly intended as a bid for the political sympathies of female, white, middle-class suburban consumers,” Lizabeth Cohen writes in her book A Consumers’ Republic. “But his administration was caught off guard when these women asserted themselves outside the voting booth.”

Assert themselves they did. Groups kept popping up from Buffalo to Baton Rouge, with names like entries in a cleverest acronym contest: YELP (You’re Enlisted to help Lower Prices), MILK (Mothers Interested in Lower Kosts), and several variations of HELP (like Housewives to Enact Lower Prices, Home Economists for Lower Prices, and Housewives Enraged - Lower Prices) .

Even dense, pompous executives started to realize something was happening. It was time to stop smirking at the housewives and do something. While it’s hard to track, anecdotal reports mention price wars breaking out wherever the housewives went on the march. Then, in November, Safeway announced they’d put an end to the highly contentious game promotions. “We don’t think they have raised prices,” said chairman Robert Magowan. “But if the housewife thinks that, we won’t fight her.”

Don’t make me come in there, little mister! These New York moms have had enough

The fighting kind

What brought the housewives’ revolt to an end? Inflation cooled off. After the 5.6% increase in the year leading up to October 1966, the CPI for food dropped 1.7% by April of 1967. By then, the picketing moms had disappeared to the point that an Associated Press story could ask, “Remember the housewives’ rebellion against supermarkets last fall?”

When asked at the time if the protests had anything to do with prices easing, Portland grocery manager Rollin Killoran conceded, “Could be… They brought attention to the competitive factor… They made us more aggressive pricewise.”

The protestors themselves were less sure. A New York Times piece pointed to the prices that had dropped - butter from 86.3 cents a pound to 84.9 cents, eggs from 62.6 cents a dozen to 60.3 cents - but also concluded that the movement had fizzled out into a dispirited cynicism. “As soon as we turn our backs, they’ll go back up,” said Rose West, while another protester said “We aren’t politicians, we’re housewives. Some housewives may be fighters, but it’s hard to get enough of the fighting kind to fight over the same thing at the same time.”

They’re being too hard on themselves. The housewives’ revolt of 1966 was brief and its direct impact limited. But it was an early education for millions of American women that there was power in their shared identity as consumers. (Almost half of protestors, one survey indicates, were between the ages of 26 and 35.)

This consciousness would flare up again in the 1973 meat boycott and keep bearing fruit in the countless gains of the consumer movement in the 1970s. And within a few short years, those smug grey establishment blowhards would learn that shrugging in the face of inflation is a great way to lose customers, credibility, and even the White House. Not bad for a bunch of housewives.

I love reading about unlikely protesters—it often sparks change, or at least forces a response. I read The Power Broker earlier this year and there’s a similar first-crack in Robert Moses’ wall of power when his parking lot plans push the moms at the park playground to block the bulldozers with baby strollers.

Got any memories of past unusual, or unusually successful fights against grocery stores or other companies? Join us in this week’s Shoddy Goods Chat.

—Dave (and the rest of Meh)

The prices never go up on these Shoddy Goods stories:

- 10 comments, 12 replies

- Comment

I’m old enough to remember grape boycotts. The most famous one is of course Cesar Chavez

The 1965-1970 Delano Grape Strike and Boycott – UFW https://share.google/dyW9ltgyBfqNX2Syr

UFW Chronology – UFW https://share.google/eos76fAVCYQgAzZyc

But therecwas more than one

In the museum of activism, there’s a chunk of floorspace highlighting the triangle shirtwaist fires among other oppressive work conditions (British chimney sweeps, early Ford factories) that pushed the idea of a disposable workforce.

https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_Shirtwaist_Factory_fire

(The owners were found not guilty on charges of knowledgeable manslaughter, but guilty on paying damages. The damages were about $75 per casualty - $3000 in today-money. The owners then collected insurance… To the tune of $400 per casualty - $13000 today - meaning they profited on their workers’ corpses.)

@pakopako Interesting. My grandmother was a survivor of the Shirtwaist Factor fire. She was on the last elevator ride to make it down safely.

@pakopako and theyre returning to this again!

[1994 story/prices] When I lived in the Detroit suburbs, my favorite coffee cost $2.39 at Kroger. One day the price jumped to $2.89 so I put it back on the shelf. 30 days later the price dropped back to $2.39. Obviously no one would pay that price. Then I moved to a northern suburb of Chicago and experienced sticker shock. My coffee cost $3.54 at Bannockburn Dominick’s and I cried real tears in the coffee aisle. Once a month I drove back to visit my mom and filled my car with coffee and other items that were outrageously priced in Chicagoland. Gradually I realized that the customers at Bannockburn Dominick’s were wearing full length minks. At the same there was a scary article in the Chicago Tribune saying the price of milk was different at each and every Dominick’s and would soon go to $10/gallon. A suburban woman was quoted as saying, “If the price is $10, I don’t care, I can afford it.” So I found another Dominick’s in Buffalo Grove and, lo and behold, my coffee was $2.89 at that location. Eventually I went further afield and found a Kmart in Vernon Hills where my coffee was, once again, $2.39. Sadly I didn’t visit my mother as much after that.

@mdiaz If I recall, Dominicks was also at the forefront of the paper-to-digital coupon revolution, pushing their store cards with “personalized price coupons”. At first blush, it seemed legit, giving customers more “sales” on more items… until you started tracking your personal “deals” over time and comparing against those offered to other customers.

Turns out the store was just using some smart data scientists and customers’ harvested personalized shopping histories to make a system in which the store got rid of sales for the general public (gotta scan that store card first to get any sale at all) and then used the computers to fine-tune the screws to the customer pain point, giving discounts just big enough for an individual to bite at and not a literal penny more.

@Turken Interesting!

The Nestle boycott. Back in the 70s they were pushing infant formula in areas with poor sanitation, unclean water, and poverty. They would give away enough of this “awesome, healthy western product” to screw up breastfeeding, then start charging. And babies got sick and died from malnutrition (parents had to heavily dilute the formula to afford it). Nestle didn’t care as long as they were profiting. I still won’t buy Nestle products.

VAN GOGH! MANGO! TANGO! AWESOME!

@krez56 around the same time there was a quieter boycott of Carl’s Jr related to his refusing to promote female workers to management/supervisory positions. it overlapped with the LGBTQ+ boycott for his support of Briggs and related.

Women organized bread riots during the Civil War, most notably in Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_bread_riots

So can we get housewives and househusbands along with those of no spousal persuasion to boycott irks that cost more than

$5$11, no other purchase necessary and win?Besides table grapes, (RIP Caesar), there was the tampon boycott! Women know how to organize!

/showme a beaming Mother Jones

@luseruser that’s usually the trend. The first computer programmers needed sharp organized minds… which meant loom workers and mathematicians who were I believe all women.

@luseruser I like our /showme as much or more than the next person, but if you’re looking to show a real person, might as well use an actual photo of 'em right?

/image Mother Jones

/showme housewives in revolt

/showme chipmunks in revolt

@mediocrebot Of course the sign has no words. Chipmunks can’t read or write.