ETAOIN SHRDLU

25He gets around. Part 1 of 2.

This is the latest installment in a regular series of researched and reported stories that @dave asked me to write about things of broad interest to the community. Previous articles have tracked down the history of SHOUTY CAPS and why the > became a symbol to cite replies in forums and email.

You may have seen the “name” Etaoin Shrdlu as a joke you clearly didn’t get. It shows up in Mad magazine as a repeated goof, and you have probably seen it here and there in old humor essays and as design elements. One of the Meh forum regulars even uses it as their handle.

Its origins take us back to the 1800s, starting with the heady days before typewriters existed. Why would Etaoin Shrdlu be connected to typewriters, you ask? Look down at your keyboard, and you’ll get a very vague hint.

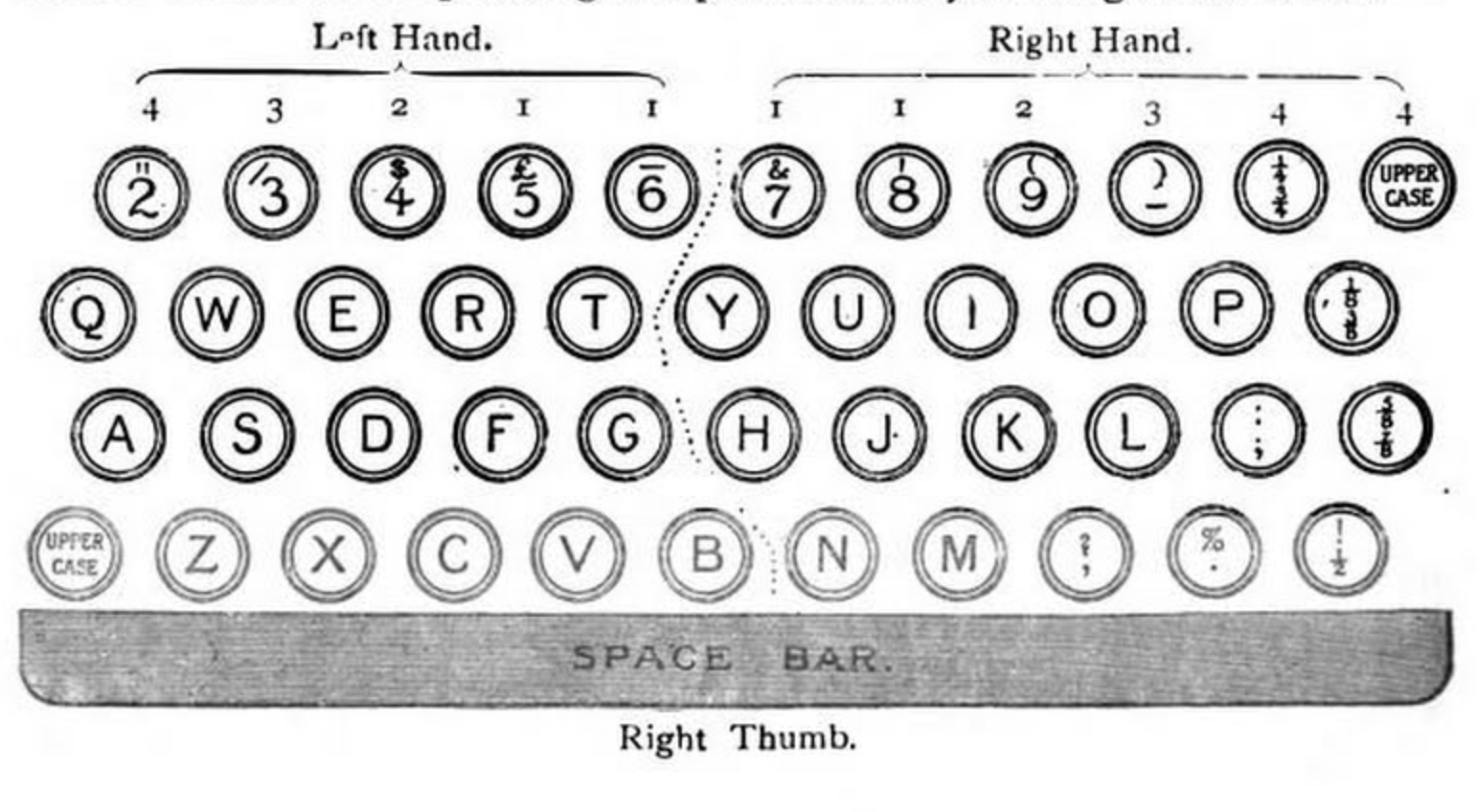

If you’re in North America, enter characters in English, and have a “normal” keyboard, you already know what you’ll see: QWERTY at left. The home row, you might not remember, is ASDFG and HJKL;. If you’re a Dvorak keyboard user, however, and don’t you feel appreciated right now, the home row keys are AOEUI and DHTNS.

Dvorak uses letter frequency to distribute characters around the keyboard, and there’s the clue. But let’s dive into the past to find the whole story.

The key is the telegraph

Buttons that you mash to make a character appear on paper is a relatively modern invention. They first appeared with typewriters, which went through a furious stage of development in the 1800s. Typewriters only became truly perfected for mass production in the 1870s—maybe not really until the 1880s if you believe the accounts written at the time about how frequently those early models broke down and require repair or replacement.

Before the spread of typewriters, everything was written by hand or composed in metal or wooden type by human typesetters. Even the best-trained pen writers could only produce about 10 to 25 words per minute, the latter when they were blazing. Telegraph key operators could send and receive at much higher word rates, making it a mismatch for taking down incoming messages. But even the earliest typewriters could quickly let barely trained users hit rates far faster than 25 wpm. The typewriter keyboard was seen as a mechanical amplifier of mental power.

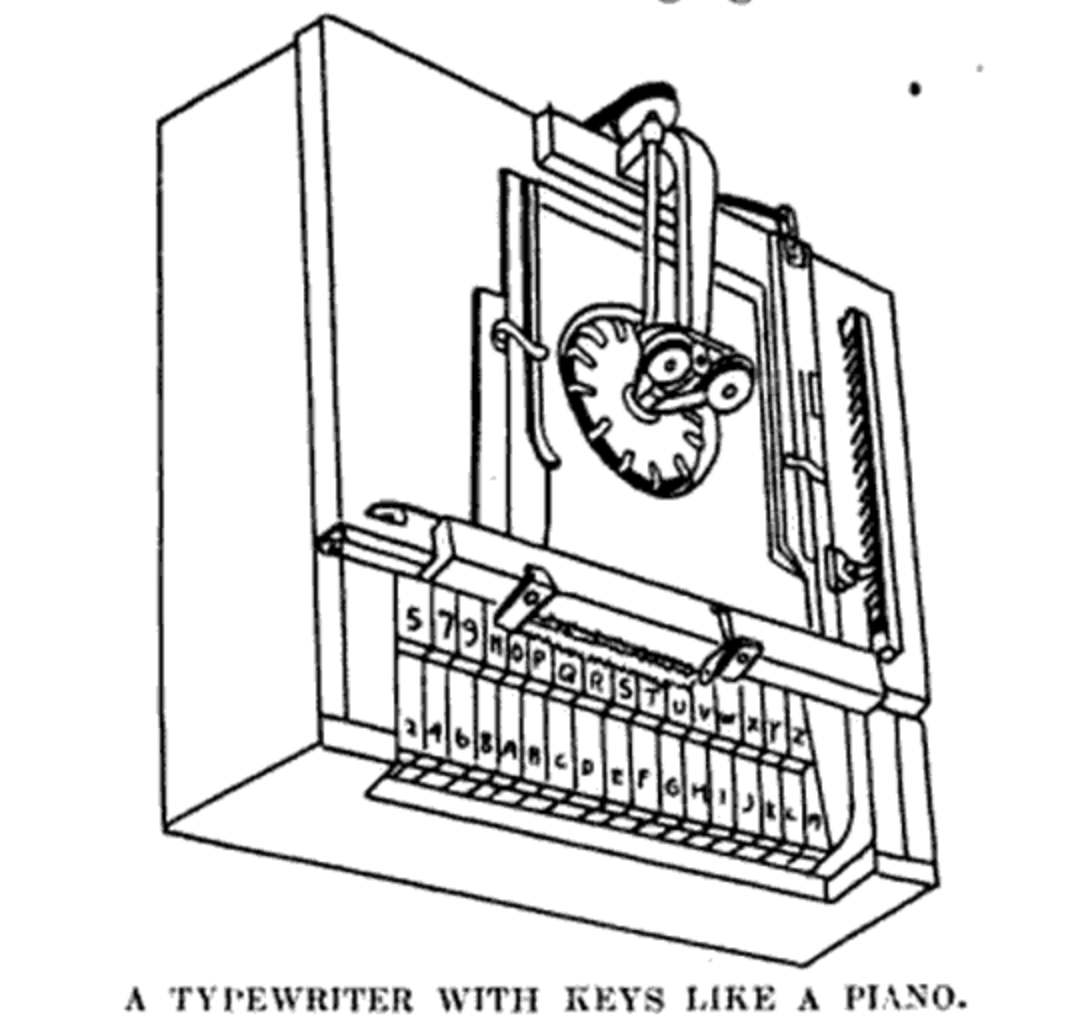

Hundreds of typewriters were being prototyped at the same time across the mid-1800s. Even when the froth subsided later in the century, there were still plenty of competitors. The only antecedent for a keyboard would have been a musical instrument, and some typewriter engineers compared their methods to playing a piano or a harpsichord.

Some of these early keyboards had a distinct piano feel, with two rows of keys arranged like a organ and in the order:

3579NOPQRSTUVWXYZ

2468ABCDEFGHIJKLM

This connection continued to be made long after typewriter keyboards had no resemblance to pianos. In The Phonographic Magazine in 1895, its editor writes, “An observer of the peculiarities of many speedy typewriter operators said to a Sun reporter that in almost every instance the most rapid were piano players.”

Over time, keyboards migrated from piano-like keys, along with dials, levers, and peculiar top-down hemispherical arrangements to a more compact multi-row format. Advantages in mechanical engineering allowed designers to make more and more complicated interconnections between keys and the typebars that contain the letter. These denser arrangements allowed for more keys, an advantage doubled with the addition of a shift lever, which could switch between different characters on a single typebar.

When the Sholes and Glidden typewriter went into mass production in the mid-1870s, it settled things down. It had a QWERTY layout—which was not designed to slow typists down, regardless of what you’ve heard and endless articles on the topic. Keys were rather arranged to serve the abovementioned telegraph operators, who were frequent beta testers, and who found more alphabetically ordered layouts inefficient. Because it was the first typewriter to make commercial inroads, it ultimately became the layout, especially after five typewriter companies merged in 1893, and all relied on the layout. (Some minor variations disappeared over time.)

You know, of course, about the Dvorak layout, created by August Dvorak and William Dealey, who patented their different keyboard layout in 1936. Instead of using QWERTY, Dvorak was optimized around letter frequency. This allegedly improved typing speed, but, as with all keyboard myths, it turned out to be less than reliable: in many studies, Dvorak typists aren’t faster than QWERTY ones.

But Dvorak and Dealey hadn’t pioneered letter frequency as a keyboard strategy. We have to return to the 1880s for that.

Continued In Part 2:

- 4 comments, 1 reply

- This topic was locked by dave

@shrdlu - they’ve outed your origin story.

I commented over there, but thought I’d add it here as well.

Terry Linograd called his program SHRDLU. It is also known as Blocks World. I should point out that the Linotype is set up for the frequency of the letters in American English, specifically. Those Britishers are far too fond of sticking in an extra “U” here and there. You know, colour vs color, etc. etc…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHRDLU

http://hci.stanford.edu/winograd/shrdlu/

http://hci.stanford.edu/winograd/shrdlu/name.html

Life remains ever interesting, although I am getting to be old.

@Shrdlu

Happens to the worst of us.

/giphy yawn fest

I’m going to lock this thread so all the comments can be in one place, over on part 2:

https://meh.com/forum/topics/etaoin-shdrlu-continued