ETAOIN SHRDLU (continued)

22What the Shrdlu, Etaoin talking about?

Etaoin Shrdlu doesn’t come from the typewriter world, but typewriting history helps explain its emergence. Typewriters and hot-metal typesetting machines, used to push sequences of type molds together through keyboard action and then cast those moulds in hot metal, evolved during the same period.

One man, James O. Clephane, funded and helped beta test Sholes and Glidden typewriter designs in the mid-1800s and was a key mover in what became the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, the first maker of practical hot-metal typesetters. Clephane was a famous stenographer, friend of Abraham Lincoln and other presidents, in an era in which accurate notetaking and representations of someone’s speeches and of court proceedings could actually make you a celebrity.

His father was a printer, so Clephane had insight into that side of things. And, like telegraphers and other professions, he and other stenographers wanted a device that would let him turn his shorthand notes into something legible to others. But he also wanted the output to be persistent for record-keeping, and, most importantly, potentially reproducible without the additional costly, time-consuming, and often impractical step of typesetting.

This led him to fund several successive ventures, some of which were typewriters and some were keyboards that would result in a lithographic surface that could be used for printing or for making a typed-out papier mâché mold that could cast a full sheet (a plate) of type. None of that panned out until he met Ottmar Mergenthaler, a gifted machinist, who took the mold idea and radically transformed it. Instead of papier mâché, Mergenthaler’s Linotype would use brass matrices from which type was cast.

A typesetter sat at a Linotype, which had magazines (compartmentalized containers) fitted above it, fed by gravity, full of molds or matrices. As the compositor typed, molds fell through channels to line up in a composing area. When the line was finished, pressing a bar sent boiling lead rushing in to cast a line.

That’s all very interesting to those of us obsessed with type and typesetting, but what keyboard layout did Linotype use? QWERTY? No. It used one that predated Dvorak for relying on letter frequency. And two slightly diagonal rows close to the center of the keyboard were the 12 most frequently used letters in the English language in order of frequency: ETAOIN SHRDLU separately in upper and lower case.

Finishing a line with a flourish

Even as typewriters were consolidating around the QWERTY layout, plenty of other approaches remained in use, and Mergenthaler had his own ideas about everything. But it also made sense, because his Linotype magazines had to have a single matrix for each letter that would be set in a line. At the end of a line, an operator would trigger distribution, which used a remarkable system to return the matrices back into their proper slots in the matrices for re-use, but the compositor could be setting a new line while that happened.

The magazines were loaded with matrices corresponding to frequency and it would make the same sense that the keyboard would be organized around the same lines: the letters the keyboarder would type most often. Forget ergonomics: the machine was dominant and people would conform.

But we finally get to the crux: wherefore art though, Etaoin Shrdlu? When a typesetter would make a typo or other error, there was no backspace key. A matrix could be removed by hand, but that was inefficient, as was rearranging letters. And incomplete lines were harder to set because of how lines were justified, or had all their spaces made of equal width to fill a column flush on the left and right.

Instead, a typesetter would run their fingers down the rows e, t, a, o, i, n, s, h, r, d, l, u, adding spaces as necessary until the line was filled. I’m sure it was melodious, the matrices falling down in order, too, over the din of this mechanical wonder that occasionally strafed its operator with squirts of lead.

Because the Linotype set each line as a separate piece of metal, called a slug, he or she could have removed an offending line, or expected a proofreader to do so in organizations that went through proofing. But it was missed often enough that newspapers, magazines, and even Linotype-set books would have etaoin, shrdlu, cmfwyp, and other lines and combinations appear by accident. For fun, search on each of those terms in Google Books, and you’ll see what I mean, and see examples at the end of this post.

You don’t see these errors as frequently in books set in hot metal, because most books were set on a Monotype, a not-much-later competitor. Instead of casting a “line or type,” the Monotype was about “mono”: it cast each piece of type individually in a clever fashion. A typesetter sat at a keyboard that let them tap out pages at a time, which were punched as dot patterns in a roll of paper tape. This tape would be carried to a casting machine that read it (using pressurized air) to cast each letter from a matrix case. Errors could be fixed in a variety of ways, including swapping out individual pieces of type. And, in any case, the keyboard was QWERTY.

The Etaoin Shrdlu era ended as Linotypes and later competitors with the same approach hit the scrap heap. And digital phototypesetting systems allowed correction. I worked on one at my high-school newspaper that also set just one line of type at a time—but the keyboard had a delete key.

Examples of historical keyboard misprints

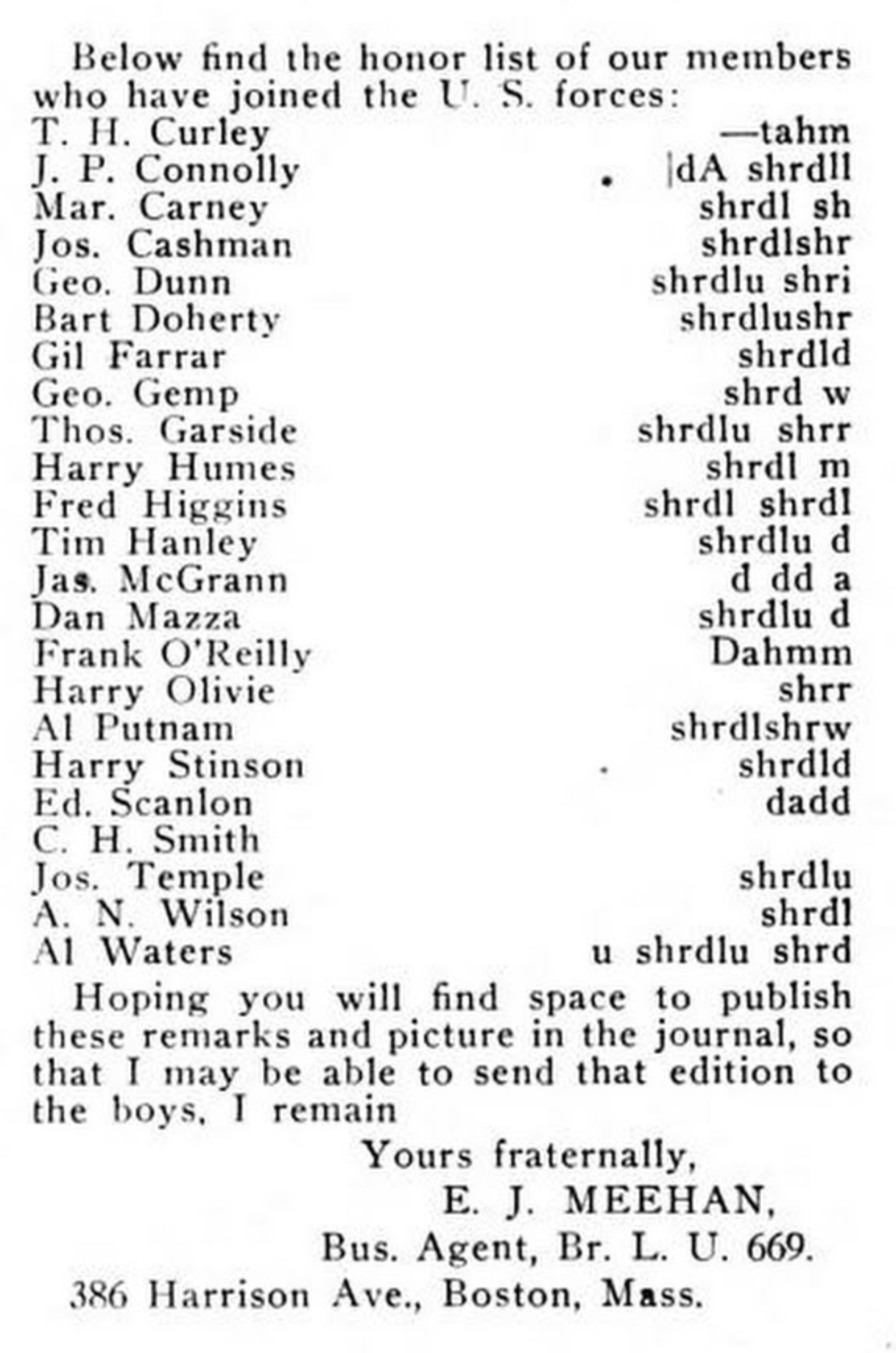

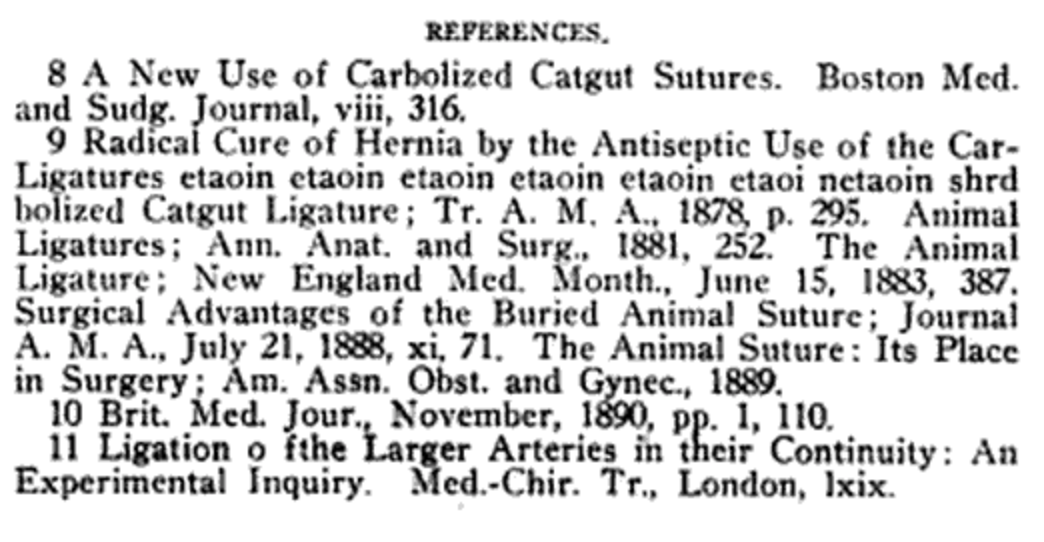

For your edification, more examples of Linotype insertions in old books and magazines.

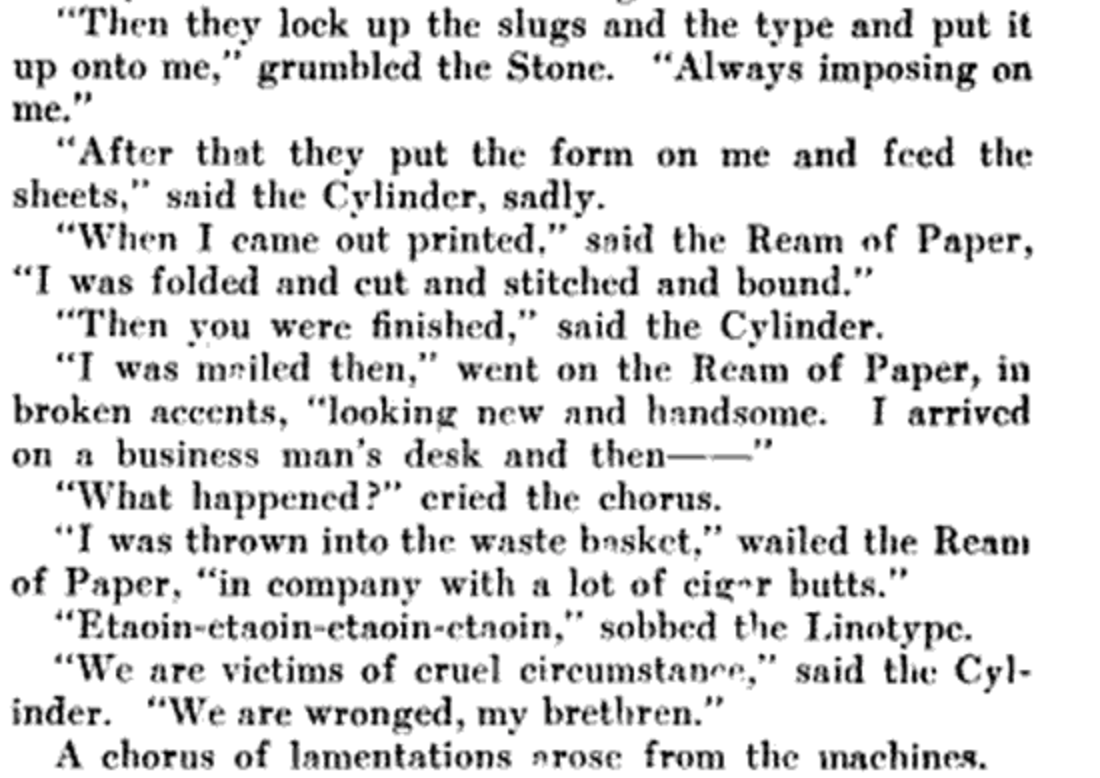

And also read the bizarre poem, “Doctor, the Chloroform,” in The Typographical Journal (March 1912)

- 7 comments, 18 replies

- Comment

Carbolized Catgut Ligatures is gonna be the name of my next band.

Terry Linograd called his program SHRDLU. It is also known as Blocks World. I should point out that the Linotype is set up for the frequency of the letters in American English, specifically. Those Britishers are far too fond of sticking in an extra “U” here and there. You know, colour vs color, etc. etc…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHRDLU

http://hci.stanford.edu/winograd/shrdlu/

http://hci.stanford.edu/winograd/shrdlu/name.html

Life remains ever interesting, although I am getting to be old.

@Shrdlu It’s funny that the “Name” page refers to the typewriter keyboard as “QUERTY”. I’m wondering whether that’s a mistake because it’s almost impossible to type any letter but “U” after a “Q” or whether the author learned the term by ear and spelled it phonetically.

@Shrdlu is it wrong that I consumed your post because I have a few manual typewriters? I think a collection is too strong a word with only 25 or so. Cause having a collection of manual typewriters is just weird, man. I did own an 1874 Sholes and Glidden for a short time, it was not as ornate as some of the later originals. It was serial number A530. Crazy to think that keyboard as one of the first few hundred still influences the written word. Sholes and Glidden and Carlos all lived and worked in Milwaukee and as a lover of my college town, I was intrigued to learn “the first commercially successful” typewriter was invented here. In fact, there were originally a large number of typewriter manufacturers in Wisconsin (Odell, … and others ). They were made in Oshkosh, Milwaukee, Fon Du Lac, and others. Ohio, New York, Illinois and Pennsylvania were prolific manufacturers of typewriters, too. I still have many beautiful models, like my current favorite, the Franklin 7 with its curved keyboard. Okay, I feel geeked out enough. Happy to carry on but feeling like everyone’s left the room…

@SSteve I have seen that page, over the years, and never noticed that it was QUERTY instead of QWERTY. I am sure it’s been called to Winograd’s attention, but equally sure that it was left on purpose. I suppose it goes hand in hand with the “SHDRLU” part on the title above (which hurts my eyes, @dave, aka as the little rat who locked part 1 from further comments).

@Shrdlu Some people are cursed with perfect pitch. I’m cursed with proofreading everything I read. But I didn’t catch “SHDRLU” in the title of this post. I’m not surprised you did, though.

@Shrdlu Thanks, fixed it.

To anyone who’s interested in Linotype history, I highly recommend Linotype: The Film which was the first Kickstarter Project I ever backed back in 2010. It’s not only historical and interesting but also surprisingly warm and touching.

@glennf I think one of us is stalking the other because we keep running in to each other here, on Kickstarter, on TidBITS, on your blog…

@SSteve Ahoy, ahoy! I highly recommend Graphic Means and Pressing On, both of which are unfortunately currently only on the film-screening circuit, but which are on track to digital download and disc in 2018. Graphic Means is about the phototypesetting era, and it captures it beautifully. Pressing On is about how the love and knowledge of letterpress are being transferred generationally.

@glennf Those both sound great. I hope you’ll let us know on your blog when they become available.

@SSteve I will! I want to do like a film festival of the eight or nine films now available about letterpress printers and type/graphic design production. Helvetica, Linotype: The Film, Making Faces, Type Face, etc.!

@glennf That sounds fantastic. Hopefully I could tie that in to a visit to Seattle to see our niece. It has been a couple years and Seattle is one of my favorite places to be.

@SSteve Here’s something else to add to the history (and my personal favorite):

https://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2014/11/13/1978-farewell-etaoin-shrdlu/

https://www.nytimes.com/video/insider/100000004687429/farewell-etaoin-shrdlu.html

(The video above lasts about 30 minutes, but remains fascinating…at least to me, it does.)

@Shrdlu I loved the video, thanks for sharing it!

@glennf Fascinating! Thank you!

I worked for a company that produced a daily and weekly regional construction news publication that was still using three Merganthalar linotype machines until the late 80s. One of my journalism teachers essentially called me a liar when I mentioned it in class so I had to bring in a slug with his name on it to prove it.

The typists were (appropriately) terrified of computers and that they might eventually be replaced by them.

They were, of course. Running Quark on Apples was a tad faster than waiting for slugs to be re-cast to correct typos.

I don’t know how many other Linotypes are still operational and viewable by the public, but for East-coast types who are interested in such things, the Baltimore Museum of Industry has one in their print shop exhibit which AFAIK is still demonstrated as part of the guided tour.

@brhfl There are a surprising number of them around, but, as you wonder, not readily available to the public. A lot of hobbyists, small shops, and tiny museums/etc have them, and you have to catch the right hours. In Portland, one day a month, you can visit the C.C. Stern Type Foundry, which has a whole Monotype composition and casting system set up. I know that Stumptown Printers in Portland have a working Linotype, so watch for open houses if you’re there or passing through!

@glennf Do they still use molten lead? It seems like that would be a health issue. But now I have yet another reason to make it up to Portland.

@SSteve They do. (Technically, an amalgam of lead, antimony, and tin. Antimony is super toxic.) But there are handling guidelines and ventilation. Far better than the bad old days — typesetters in the pre hot-metal days died on average at age 28 in 1850.

@glennf How much did that have to do with typesetting, though, versus how much that had to do with it being 1850 and life expectancies were pretty short anyway?

@jqubed Life expectancy was about 38 to 44 for the general population, which is terrifying horrible when you stop to think about it. So these folks were dying 10 to 15 years earlier on average. By about 1920, typesetters had about the same life expectancy as everyone else, due to improved working conditions — even handling boiling lead and breathing its fumes, amazingly.

@glennf Huh. I’m already North of 50.

/giphy winning

@brhfl there’s one that runs at the Iowa State Fair each year. I always stop by and get a souvenir slug with my name on it.