CAPITAL CRIMES, Part 2: Usenet has no CHILL

16In Part 1 of this article, I took us back in time to find the first recorded description of all-capital type being described as shouting. In Part 2, first we head even further back, to talk about the separate paths of lowercase and uppercase, then shift to more recent times—to the dawn of Usenet discussions about YELLING.

Letters Came to a Fork in the Road and Took It

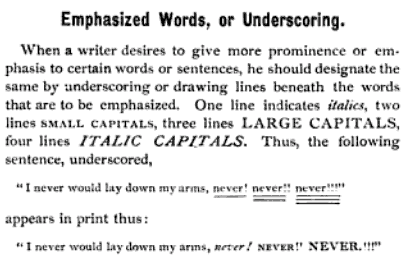

To the modern eye, uppercase and lowercase letters (written in industry shorthand as u&lc) have a strong relationship and appear natural together. But that’s a result of a bifurcated evolution that later fused together, imperfectly. Capitals (also known as “majuscules”) arose from stonecutting. “Capital letters were a symbol of the power of the Roman Empire, which left its traces over most of Europe,” James Mosley writes via email when I ask him for the long, long view on this topic. Mosley is a renowned librarian and historian whose work across several decades centers on the history of printing and letter design.

Lowercase, called minuscule, developed from written versions of capitals. While the main body of most small letters is the same height, portions may rise above and drop below a baseline, an outgrowth of how they are written by hand, especially in smoothly flowing script. (I promised above to explain small capitals. As a typographic refinement, they are used when a run of capitals is needed in the middle of mixed-case text, as in a book or magazine article, and aid legibility. Drawn separately from true uppercase, they fit into the height of the lowercase letters, called the x-height.)

Eventually, uppercase and lowercase merged into a single alphabet. Mosley notes, “The ‘binary’ writing system (caps and lowercase) is a bit of a nuisance, but since we have it we may as well make the best of it.” He says that in more modern times, telegrams were written tersely (to save money) and appeared only in all caps—and brought bad news. “[This] has tended to color our reaction to information that is given in capital letters, and so did public notices in the name of authority and backed up with a threat of punishment, which were always in caps (NO PARKING or NO SMOKING).”

It’s rare to see a stretch of full capitalization in handwriting, except in block printing, as it would be somewhat illegible, as well as tedious and slower to write. Movable type made runs of uppercase feasible, and often preferable, as it required more work to pick among letters of mixed case. (Uppercase and lowercase in fact refer to a typical arrangement for handset type, in which cases contained type in cubbyholes. The lower case had small letters, among other symbols; the upper case, the capitals.)

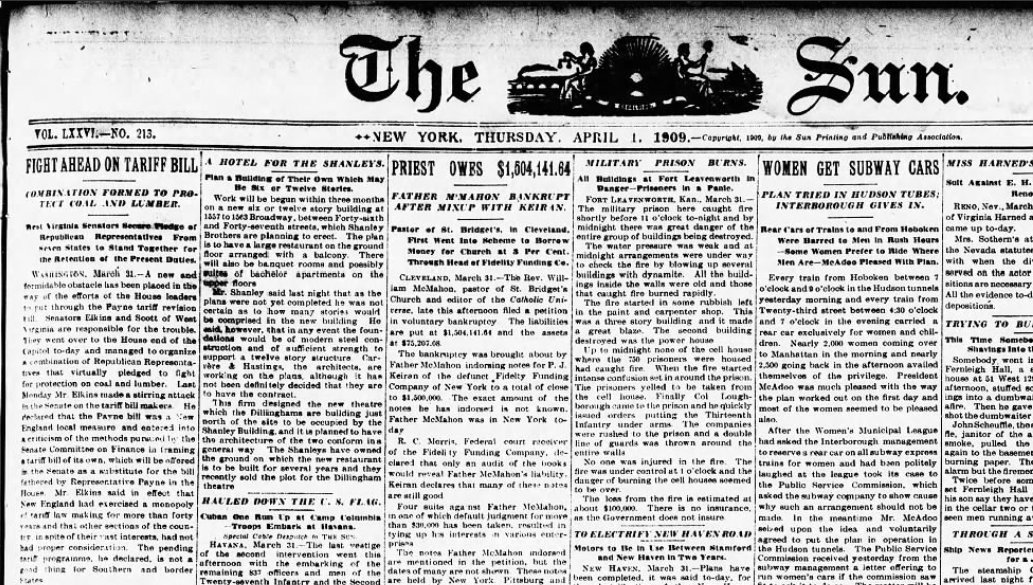

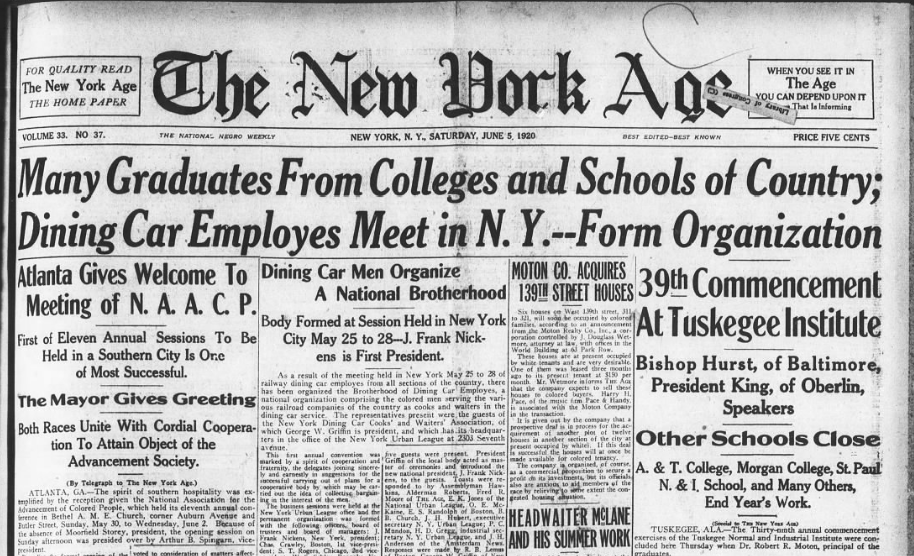

Paul Shaw, a design historian, points out that newspapers tended to use all-capital headlines through the 1910s, when typographer Ben Sherbow, at the New York Tribune, pushed for the use of mixed case, among other layout changes, for better legibility.

It’s just possible that the decreased use of what the newspaper world called “screamers,” a good synonym for shouting, led to less association between uppercase letters and yelling. I can’t make a solid case for that, except for the quiet period until the 1980s.

But a new way to type seemed to bring on the noise.

Headlines in The Sun, 1909, were all yelling.

By 1920, this New York Age front page shows a more typical mixed case.

A Capital Idea Returns

At the outset of Part 1, I noted that if you’re reading this you already know the convention. But where did you learn it? Who first told you, or how did you understand, that uppercase implied loudness?

I asked Dave Decot this question. He studied computer science from 1979 to 1984 at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) and worked for many years in information technology. He recalls, “I would have to say I first saw that other people were using all caps for emphasis and to shout at each other while at CWRU.” Decot says that in high school, a few years before, they had shifted from teletypes to uppercase-only CRT terminals and then, his last two years, to more advanced HP2645A terminals that had mixed upper- and lowercase.

Now why am I seemingly quoting Decot at random? He also has the quiet distinction of being the first person on the modern Internet to explain in detail the convention of all-capital yelling (and a couple of other conventions). The New Republic story from 2014 noted above cited his March 1984 post:

Well, there seem to be some conventions developing in the use of various

emphasizers. There are three kinds of emphasis in use, in order of popularity:

1) using CAPITAL LETTERS to make words look “louder”,

2) using asterisks to put sparklers around emphasized words, and

3) s p a c i n g words o u t, possibly accompanied by 1) or 2).

I contacted Decot, and he was surprised and pleased to discover his historic role. “I was then in the slog of completing my computer science thesis (an ASCII-based music description language, compiler, and graphical sheet music formatter, if you must know),” and to his recollection, he picked up these definitions at CWRU, not in high school.

The most significant preceding mention comes indirectly in 1982, when Steven McGeady posted “A Plea” in the net.general group:

At the risk of sounding like I am flaming, let me state a simple fact: MODERN MAILERS WILL NOT HANDLE PATHNAMES AND SITENAMES WHICH CONTAIN CASE DISTINCTIONS. MANY SITES CANNOT REPLY TO SITES WHO HAVE UPPER- CASE NAMES.

(McGeady was at Tektronix at the time and is well known for a later stint at Intel, when he was a key witness against Microsoft in its antitrust lawsuit.)

After Decot’s post in March 1984, I found a few interesting citations. Another from March, in response to a post by well-known programmer and tech writer Randall Schwartz defending his copyright, complains, “Schwartz is really looking to be argumentative and shouting, terminal-style, a lot.” (This is also a good early citation for tone policing.)

In July 1984, in alt.flame:

am i getting carried away here, or will maybe all of this ranting and jumping up and down (if it’s in caps i’m trying to YELL!) will knock some sense into some people.

And in November 1984, someone asks, “Do all the CAPITALS suggest that you are trying to shout?” in net.abortion.

Keep It Down

There’s no drama in discovering more historical evidence for the use of shouting capitals, but it’s always rewarding to find a through line from modern culture that goes back not just dozens, or even hundreds, but possibly thousands of years. Our use of technology for communication is much more similar to that of preceding generations than it seems at first glance. But I rest comforted knowing that people were just as irritated by SHOUTY CAPS 160 years ago as we are today.

Glenn Fleishman is a veteran, grizzled technology reporter who has written regularly for the Economist, Macworld, Fast Company, and MIT Technology Review, and was the editor and publisher of the now-defunct The Magazine.

Related Stories

Kashmir Hill spent a week typing in all capitals and lived to tell the tale.

The podcast 99% Invisible mentioned the history of the Caps Lock key in passing while discussing the #.

My friend and colleague Tom Standage, a deputy editor of the Economist, has written several books tracing the connections between old and new tech. Most apt here are Writing on the Wall: Social Media—the First 2,000 Years and The Victorian Internet.

- 8 comments, 10 replies

- Comment

great stuff here!

i'm also wondering what happened to the Dining Car Men's national brotherhood.

@carl669 That's part of a rich racial tapestry of who worked on trains. If you want to go down a rabbit hole about post-Slavery jobs? The Atlantic has this story about the fraught history of men's beards.

@glennf great. now i'm definitely not getting any work done this afternoon. i'd blame you, but i am required by meh bylaws to blame @medz.

Another great reading!

I have to admit that my grammar was honed from reading Usenet groups back in the days.

Sadly, it seems that I'm in the minority. Many more folks honed their grammar from cats.

@narfcake I haz grammar

@compunaut

http://shirt.woot.com/offers/learning-my-grammeh-1

http://shirt.woot.com/offers/my-grammar-is-purrrrfect

http://shirt.woot.com/offers/destroying-grammar

@narfcake I learned grammar in school, but it wasn't till I found usenet newsgroups in 1994 that I learned an entirely new form of grammar.

I wonder if there'll be a chapter in this discussion of the wars over top-posting.

@glennf Another fascinating piece! Thanks so much for this.

My biggest question is how are you finding things in the Google Groups Usenet interface?

I've always heard it's a trainwreck now, but maybe not.

@dashcloud Oh, there's a secret hidden advanced search option. Google is terrible about exposing it via the Groups search interface, but if you search (ha), you can find it. Here it is, with all the grammar.

I honed my fine posting skills on various OTR USENET groups. Back in the day, we called it USENET, not "Usenet." We also wore onions on our belts, which was the fashion of the day.

But out of various USENET group FAQ's I learned that top-posting was rude. I also learned when the evil empire provided Outlook Express with USENET capability, with it's default top-posting format, that a bunch of idjits were going to start top-posting and that they would have the blessings of Micro$oft--those fuckers!

Then came those WebTv fuckers. Don't even ask.

@therealjrn Huh. That's what I get for replying to someone before reading all the comments. I used to be a regular on a newsgroup whose members were fierce on enforcing the FAQ, especially in regards to the mortal sin of top-posting. (After fighting to newgroup our patch of turf out of the lawless alt.* part of the planet and into a Big Seven group, we weren't about to cede ground to top posters.)

@magic_cave It was a glorious time m_c

@therealjrn I was a latecomer, only using Usenet as early as about 1986.

I have scheduled some time to read this next monday at noon.

Oh jeez every night after work in the 80s - I looked for the worst, most contentious newsgroups: talk.origins, talk.abortion, alt.revisionism - took out my frustrations at 1200bps. I still want to smack Canter & Siegel for fucking it all up.

The next time my son yells at me, I'm telling him to stop talking in all caps.

Maybe that'll work . . .

@glennf Not that this predates your finds, but I found this post from June 1984 joking about a subdued politician:

@dave This is fantastic. It's this kind of explicit statement of something everyone knows that's so hard to root out. I expect if I could spend a month looking at all the opinion pieces and fiction in newspapers of a certain era (maybe before the 1850s), I would probably find much more subtle examples.