Samba Glass Insulated Carafe

Our Take

- This 34-ounce real glass carafe in a plastic protective shell comes in your choice of red, white, or blue because America!- Even though it was made in Germany- Liquid stays hot for 10 hours and cold for 16 hours under normal American conditions- Push-button opening makes pouring easy, gives you powerful feeling of mastery over all liquids- Model: E504235 (without that last 5 on the end, the Google results would all be about a certain hex color, so fine, we accept the length as necessary)

Battles of the Bottle: Turning Points in the American Beverage Revolution

This July 4, we’re selling this carafe that holds liquid, in your choice of red, white, or blue. And it got us thinking about all the liquids that have defined THE red, white, and blue, and the beverage choices we as a people have faced. Here are five pivotal moments when, if we’d ordered a different drink, everything might have turned out differently:https://d2b8wt72ktn9a2.cloudfront.net/mediocre/image/upload/v1467602440/zoa4lsv45zwjw0wyczna.jpg**Booze vs. Water:** The most unbelievable legend about George Washington is that the Father of Our Country was able to stand up in that boat. The average colonial American drank three times as much alcohol as the average American today. Beer was considered food, with even kids downing a tankard full for breakfast. Diaries from the time describe the rum, wine, whiskey, cordials, cider, punch, and sherry flowing freely throughout the day. Given the state of sanitation, the seemingly weird British folk belief about water being dangerous was probably true. At least distillation killed the bacteria.As young America moved west, away from the breweries and distilleries of the settled towns, it needed its own indigenous source of hooch. Along came tree-planter John Chapman, sowing the seeds of cider up and down the thirsty frontier. Early 19th century frontier Americans drank over 10 ounces of hard cider a day. You didn’t think Johnny Appleseed was so beloved because people wanted pie, did you?https://d2b8wt72ktn9a2.cloudfront.net/mediocre/image/upload/v1467602548/akng7j3yaceluakzly0h.jpg**Coffee vs. Tea:** Of course, the beverage most closely associated with the American Revolution is tea: not leaves steeping in fine china, but crates bobbing in Boston Harbor. The British taxes on tea were a symbol of everything the colonists hated about royal control of the economy and politics in the 13 colonies. John Adams called it a “traitor’s drink”, the rebels took up coffee instead, and by the end of the fighting, one of the most enduring cultural differences between the USA and the mother country was set for good.But it would take a while yet for coffee to become the quintessential American drug. Most coffee beans available in the 19th century were months old by the time they reached consumers, not roasted well, and prohibitively expensive to drink every day. It wasn’t until steamships came along, and coffee roasting improved, that it became a ritual presence in American life.Widespread ads in the 1950s popularized the concept of the “coffee break”. Mr. Coffee led the new wave of home coffeemakers in the 1960s and 1970s, replacing the hassle and burnt flavor of percolated coffee. And, of course, the last thirty years have seen the rise of coffee connoisseurship, from Starbucks down to the French press in your kitchen. And what became of tea? It caught on with American drinkers in its own way: iced, the way some 85% of tea is consumed in the United States today. We like to think King George would still be horrified. Beer vs. Red-Blooded Americanism: As we said before, beer was already an American staple by the time of Paul Revere’s ride - indeed, Native Americans brewed their own forms of it before Europeans arrived. As you’d expect, heavy English-style ales dominated early American brewing (and breakfast).When German and Central European immigrants began arriving in the mid-1800’s, their lighter lagers proved easier to make, preserve, and ship on a large scale. From Eberhard Anheuser in St. Louis to Joseph Schlitz in Milwaukee, from David Yuengling in Pennsylvania to Kosmos Spoetzl in Texas, German-American brewers made lagers and pilseners the beer of choice for a booming, thirsty nation.Then the United States entered World War I against Germany in 1917, and the rising Prohibition movement pounced on anti-German sentiment in their own war on alcohol. “Kaiser brew” was the Hun’s secret weapon against America, the temperance movement said: no patriotic American could possibly be against banning it. By the time the fever passed and beer was legal again, the German-American brewing culture was shattered. For each of the big, familiar names who managed to revive, thousands of others went out of business forever.

Beer vs. Red-Blooded Americanism: As we said before, beer was already an American staple by the time of Paul Revere’s ride - indeed, Native Americans brewed their own forms of it before Europeans arrived. As you’d expect, heavy English-style ales dominated early American brewing (and breakfast).When German and Central European immigrants began arriving in the mid-1800’s, their lighter lagers proved easier to make, preserve, and ship on a large scale. From Eberhard Anheuser in St. Louis to Joseph Schlitz in Milwaukee, from David Yuengling in Pennsylvania to Kosmos Spoetzl in Texas, German-American brewers made lagers and pilseners the beer of choice for a booming, thirsty nation.Then the United States entered World War I against Germany in 1917, and the rising Prohibition movement pounced on anti-German sentiment in their own war on alcohol. “Kaiser brew” was the Hun’s secret weapon against America, the temperance movement said: no patriotic American could possibly be against banning it. By the time the fever passed and beer was legal again, the German-American brewing culture was shattered. For each of the big, familiar names who managed to revive, thousands of others went out of business forever. Cocktails vs. Moonshine: Prohibition also dealt a near-fatal blow to the American cocktail tradition, but with a twist (sorry, I had to to do it). Between the Civil War and Prohibition, American mixology was the envy of the world’s drinkers, with upmarket watering holes offering a vast array of sometimes simple, always sophisticated drinks made with fresh ingredients. The Martini, the Manhattan, the Old Fashioned, and the classic Daiquiri are all products of this Golden Age.Prohibition forced the best American barmen to leave the country to ply their trade. Those left behind had to make do with noxious bathtub hooch mixed under clandestine conditions. Drinking became more about getting drunk than enjoying the flavor. Cocktails became more about hiding the taste of terrible liquor than accenting the taste of fine liquor, leading eventually to the over-sweetened and/or slushy abominations on offer at the likes of TGI Friday’s. There is a silver lining, though. Those expat American bartenders brought new ingredients and styles back home after Prohibition, where there was plenty of room in the market for foreign distillers. And the necessity of cloaking that moonshine flavor meant that more Americans were open to the idea of cocktails. Now the craft cocktail resurgence has restored a lot of that pre-Prohibition cocktail wisdom. But it’s taken us an awful lot of Blue Mango Muddy Nipples to get there.

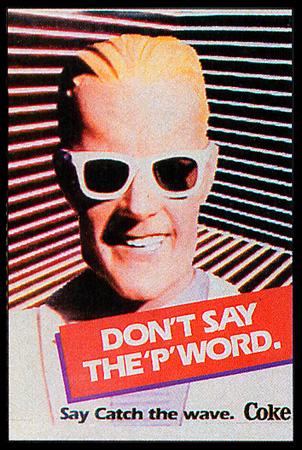

Cocktails vs. Moonshine: Prohibition also dealt a near-fatal blow to the American cocktail tradition, but with a twist (sorry, I had to to do it). Between the Civil War and Prohibition, American mixology was the envy of the world’s drinkers, with upmarket watering holes offering a vast array of sometimes simple, always sophisticated drinks made with fresh ingredients. The Martini, the Manhattan, the Old Fashioned, and the classic Daiquiri are all products of this Golden Age.Prohibition forced the best American barmen to leave the country to ply their trade. Those left behind had to make do with noxious bathtub hooch mixed under clandestine conditions. Drinking became more about getting drunk than enjoying the flavor. Cocktails became more about hiding the taste of terrible liquor than accenting the taste of fine liquor, leading eventually to the over-sweetened and/or slushy abominations on offer at the likes of TGI Friday’s. There is a silver lining, though. Those expat American bartenders brought new ingredients and styles back home after Prohibition, where there was plenty of room in the market for foreign distillers. And the necessity of cloaking that moonshine flavor meant that more Americans were open to the idea of cocktails. Now the craft cocktail resurgence has restored a lot of that pre-Prohibition cocktail wisdom. But it’s taken us an awful lot of Blue Mango Muddy Nipples to get there. Coke vs. Pepsi: As the 1800s turned into the 1900s, if you were predicting what beverage would come to define the nation by the middle of the new century, you probably wouldn’t have bet on a cocaine-laced “nerve tonic” from Atlanta. It took a sweetened formula, the convenience of bottling, and saturation advertising to make Coca-Cola a presence on the national scene - and eventually, for better or worse, synonymous with the United States itself.But not without some competition. Another Southerner, pharmacist Caleb Bradham, created his own fizzy fountain beverage in the 1890s. “Brad’s Drink” was quickly renamed for the pepsin and kola nuts in its recipe, and Pepsi-Cola was born. Where Coke was the undisputed champion of magazine advertising, Pepsi jumped on the new medium of radio in the 1920s, its catchy jingles repeated ad nauseam over the airwaves. The coup that finally brought Pepsi to Coke’s level came in 1936, offering a 12-ounce bottle for the same nickel price as Coke’s 6.5-ounce bottle.And so the 20th century in America was the century of soda, or pop, or just “Coke” - even the differences in the drink’s name are telling signifiers of regional origin. We all remember “the Cola Wars”. We all know “New Coke” is a shorthand for a disastrous change to a beloved product. We all get that “Coca-Colonization” means the transformation of traditional cultures by American consumerism. Now the sun’s starting to set on soda. U.S. consumption in 2016 dropped for the 11th straight year, to hit a 30-year-low. Its high sugar and empty calories are a prime factor in the rise of obesity, coming under tax and regulatory fire in localities around the country. Soda still dominates the soft drink market for the moment, but it’s no longer considered America in a bottle.We don’t know what comes after the twilight of soda. Maybe some goofball copywriter in 50 or 100 years will see the perfect metaphor for this era in coconut La Croix, or kombucha, or Five-Hour Energy. If the beverage battles of the past are any guide, the key to our future might be as close as the cup on your desk.

Coke vs. Pepsi: As the 1800s turned into the 1900s, if you were predicting what beverage would come to define the nation by the middle of the new century, you probably wouldn’t have bet on a cocaine-laced “nerve tonic” from Atlanta. It took a sweetened formula, the convenience of bottling, and saturation advertising to make Coca-Cola a presence on the national scene - and eventually, for better or worse, synonymous with the United States itself.But not without some competition. Another Southerner, pharmacist Caleb Bradham, created his own fizzy fountain beverage in the 1890s. “Brad’s Drink” was quickly renamed for the pepsin and kola nuts in its recipe, and Pepsi-Cola was born. Where Coke was the undisputed champion of magazine advertising, Pepsi jumped on the new medium of radio in the 1920s, its catchy jingles repeated ad nauseam over the airwaves. The coup that finally brought Pepsi to Coke’s level came in 1936, offering a 12-ounce bottle for the same nickel price as Coke’s 6.5-ounce bottle.And so the 20th century in America was the century of soda, or pop, or just “Coke” - even the differences in the drink’s name are telling signifiers of regional origin. We all remember “the Cola Wars”. We all know “New Coke” is a shorthand for a disastrous change to a beloved product. We all get that “Coca-Colonization” means the transformation of traditional cultures by American consumerism. Now the sun’s starting to set on soda. U.S. consumption in 2016 dropped for the 11th straight year, to hit a 30-year-low. Its high sugar and empty calories are a prime factor in the rise of obesity, coming under tax and regulatory fire in localities around the country. Soda still dominates the soft drink market for the moment, but it’s no longer considered America in a bottle.We don’t know what comes after the twilight of soda. Maybe some goofball copywriter in 50 or 100 years will see the perfect metaphor for this era in coconut La Croix, or kombucha, or Five-Hour Energy. If the beverage battles of the past are any guide, the key to our future might be as close as the cup on your desk.